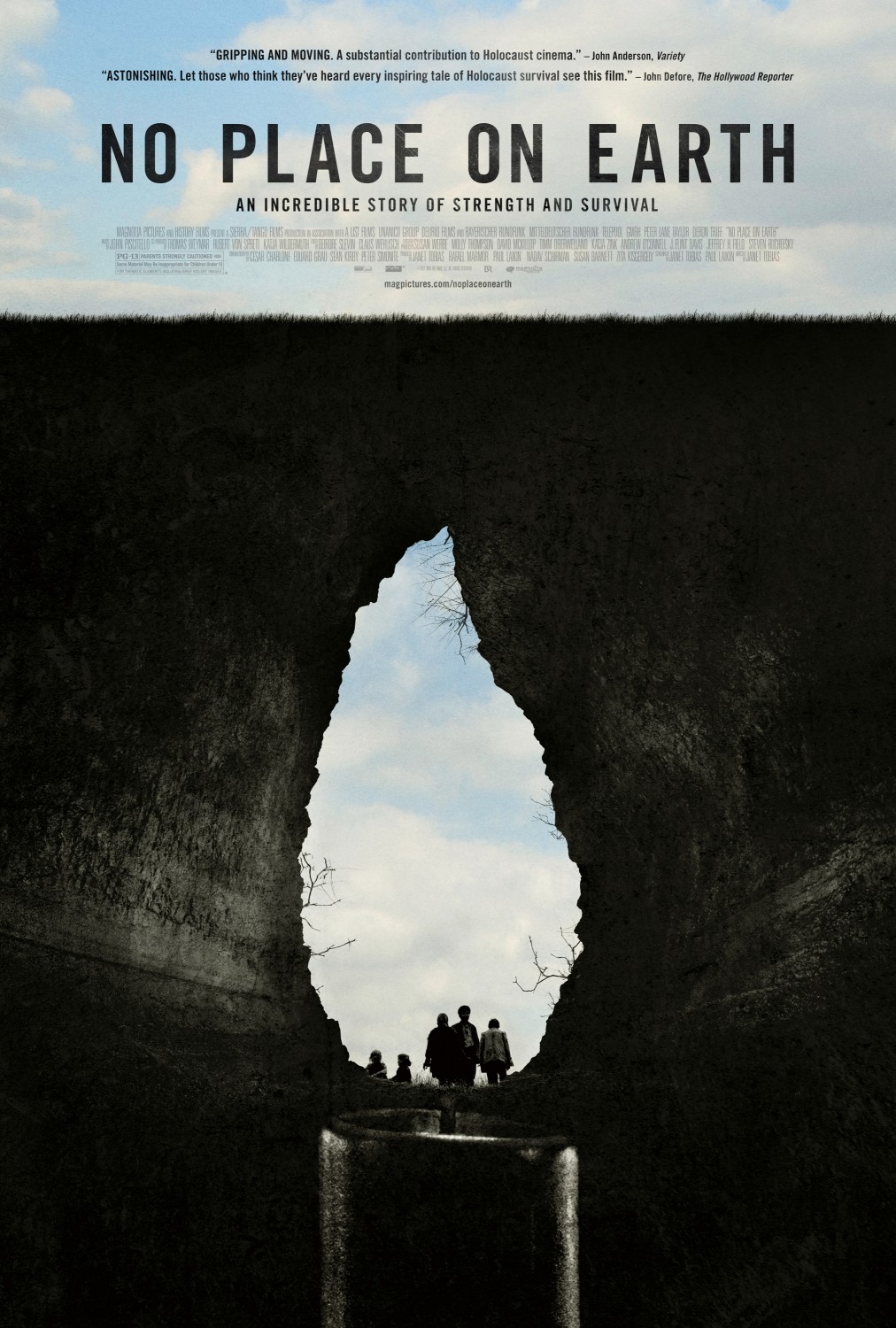

No Place on Earth is a documentary about one family's "bedtime story"; a tale of a family in World War II who successfully hid from the Nazis by hiding in two caves for 511 days straight. As filled with miracles this story may be, the events are all true, as unearthed by cave explorer Chris Nicola. Director Janet Tobias brings the story to life with dramatic reenactments and interviews with the survivors in this enthralling documentary.

No Place on Earth is a documentary about one family's "bedtime story"; a tale of a family in World War II who successfully hid from the Nazis by hiding in two caves for 511 days straight. As filled with miracles this story may be, the events are all true, as unearthed by cave explorer Chris Nicola. Director Janet Tobias brings the story to life with dramatic reenactments and interviews with the survivors in this enthralling documentary.

This is Tobias' first feature film, with her previous journalistic experience (as a producer) featured on television programs like "Frontline," and TV docs like "The Battle for America's Schools," and "MSNBC Reports: The Next War."

In this exciting opportunity, I was able to talk to three of the survivors whose story is told in the film, Sima Dodyk Blitzer, Sonia Dodyk Hochman, and Sam Stermer. For this exclusive interview, I sat down with Tobias and three of her documentary subjects to discuss the film, their incredible experience, how this family story resonates with them today, and more.

No Place on Earth opens in Chicago on April 19.

Who are some of your favorite heroes from fiction? From books, movies, etc.? Sam Stermer: I used to like Barbara Stanwyck. I was in love with the girl. When I was younger, I was in love with some people in the movies. I forgot the names. I also loved that girl, the left-handed, she was a singer, I forgot her name.

Do the three of you enjoy watching films? Do you have any favorites?

Sonia Dodyk Hochman: I like the old movies. Casablanca. I like Bogart, and also Ingrid Bergman ... No Place on Earth!

Sima Dodyk Blitzer: I think all three of us are too realistic. We could never laugh like you. Because we have gone through too much. I remember when I was in grade seven. I arrived when I was ten, and by twelve I already spoke fluent English. And when I was at school I'd watch the other kids laugh, and run around. The reason I felt this is because I had gone through so much, and I could never tell anyone anything because would they believe me that I lived a year and a half in caves? It was just too unrealistic. So we didn't speak to outsiders. We spoke about it between ourselves a lot. I wouldn't tell a classmate, even if she was my friend. It was too unbelievable. It is very hard to get into this dream land. Although, I must say, I do like Tony Curtis, because he was very handsome.

There's the saying that talking about a memory only changes the details over time. Has talking about this memory so often with family members made your knowledge of these events even sharper?

Hochman: Let me tell you something. This story hasn't changed. We speak about the same thing that we spoke thirty years ago, and sixty years ago. It is with us all of the time. If you ask me, can I feel any different now when watching the movie? I was there. When the Gestapo came out and took my sister and mother and my mother pushed me under the bed and I saw the boots and their flashlight, that fear is still with me. The fear of the Germans, and the fear of losing your loved ones, is the same. It's a little easier now, we've grown up, we have our families, but sometimes, I have a den in my house upstairs. I close the shades, and my husband says, "She's in the grotto again." And I always feel like I'm in the grotto. In the grotto we felt very secure, and very safe. We were the whole family. You turned around and you saw a grandfather or a mother, your sister or aunts. We were very fortunate. So it's always with us, we are always grateful to God that we have that. A lot of people, like my husband, he survived without anyone around him. They killed everybody, but I was very fortunate, and I am still grateful to God that we survived. Unfortunately, after liberation, my grandfather and father were killed by the Ukrainians. And that is always with me. I have a picture of my family that was taken in 1936. My sister wasn't born yet. Every morning, I come down from my bedroom, and I go into the den, and I just say hello to my mother and father and my grandmother and grandfather. This is not the norm. People don't do this, but I always, when I have a problem or anything, I'll go over and talk to my family. And I'll tell them what's happening. My children, they don't have that. They didn't live through a war with Hitler. When you live through a war like that, it remains with you. Even though I'll smile and get dressed and look for furniture just like everyone else, I am different than the others.

Stermer: I think that we were very lucky. We stuck together. We were playing golf, me and my brothers. We always talk about it. This has been going on for the last 69 years. Tomorrow [April 12], 69 years. And we always talk about it. And we said, "One day, we don't talk about it." And then we played the game. But three or four holes into the game, then we started again. This is with us, and with the whole family, every time we have a gathering, we talk about it and we'll never forget it. We didn't live under the gun. We slept in a bed, covered. We were inside, and we were going around. We were kids. We didn't realize how bad it was. We were singing. We slept a lot. I am not as damaged as the other people from the concentration camps. But we were grateful we survived and we were in the right places with the right people. Especially my oldest brother, he carried the whole family.

When you talk about this story with family members, are there ever any disagreements about facts from these memories?

Stermer: I can tell you every week, every day what happened. It stays a picture in front of me. How are these events inspiring to your daily lives now?

Hochman: My grandmother, when they discovered us, got up to speak to the Gestapo to give us a chance to hide. Whenever I am in trouble, I always see my grandmother standing there and talking to the Gestapo. She knew they were going to shoot her, but she wasn't afraid. She wanted to try to save her children. I'm a mother now, I'm a grandmother. If a terrible things happen in my life, I think of my grandmother. She stood up, and she knew she was going to be killed, so what am I complaining about? I have to get up, and I have to do this, and to do that, to help my family. And then my grandmother carries my uncle. During the war, parents used to run away from children, or children would run away from parents. It didn't happen in our family. My grandmother dragged a man of 22 years old from house to house, until one house let him in. So when I am in trouble, and I feel that this is hardship, all I do is think of my grandmother carrying my uncle. And I say, "How dare you feel bad for yourself, Sonia. You have your grandmother's blood in your veins. And you'd better get up, and you'd better do what you are supposed to do." This is the courage that she gives everyone of us.

Stermer: She always was ahead of time. I remember when no one wanted to listen to our stories. She sat down in the 1960s, when she was 70 years old, and wrote this book. The writing is like a print. She wrote 138 big pages and she did it in two months. When you look at the book, you think, how could she do that?

This story is inspiring to looking into your past, and uncovering stories. Chris was looking for a family story, and found yours. Janet, how did this inspire your own thoughts about your own family, past or present?

Janet Tobias: I sort of know all of my family history, which is a mix of Irish, Norwegian, English, and old Dutch. What it did inspire me is that has reminded me as a single woman whose career is in New York, how important family is, and at the end of the day we will do incredible things for the people we love, by depending on them, and connecting with them. We can do things we thought were impossible. I think that's a really powerful message. It was a collective group, and a collective ability. Kindness, bravery, strength, pure smarts and strategic planning were all needed, and were possible because this group stuck together.

Blitzer: When we went to Ukraine years ago, they gave us a list to be in the cave. We had to have warm clothes, and particular clothes, that was windproof, wet-proof, chill-proof, etc. I called up my Uncle Saul, and asked where I was going to get everything. And he said, "Don't you remember? You ran around barefoot, you didn't have a hat to wear. We stayed there for a year and a half and survived. Don't worry about it." We were cavers. We didn't take lessons, we didn't have the proper clothes. And yet we managed to live in two caves. And we didn't get sick, and nobody had any nervous breakdowns. No psychiatrists, and no doctors. And we survived.