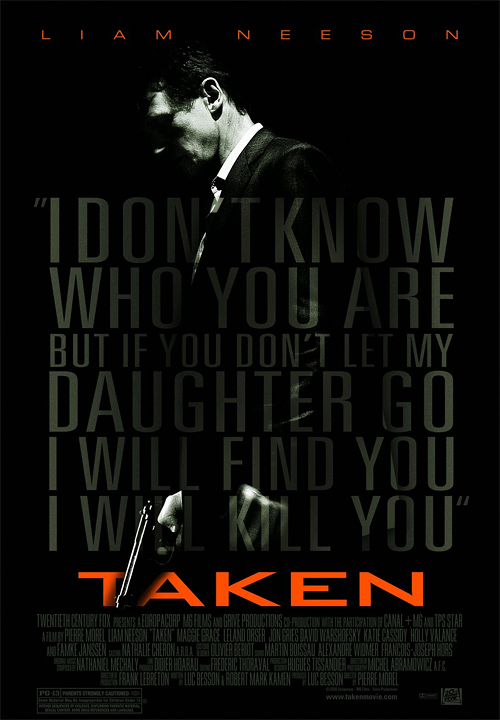

“If you’re looking for ransom, I can tell you that I don’t have any money. What I do have, are a very particular set of skills, skills I have acquired over a very long career, skills that make me a nightmare for people like you.” - Bryan Mills (Liam Neeson), Taken

When Liam Neeson was playing telephone with bad guys in 2008’s Taken, he was not just introducing himself to those who had nixed his daughter’s attempt to stalk U2 guitarist The Edge. He was inaugurating a new action hero archetype built of aged wisdom and burrowed brawn, the middle-aged vigilante assassin. (Vigilante applied here because as “one who undertakes law enforcement without legal authority,” while “assassin” fits to associations of precise violent skills.)

“If you’re looking for ransom, I can tell you that I don’t have any money. What I do have, are a very particular set of skills, skills I have acquired over a very long career, skills that make me a nightmare for people like you.” - Bryan Mills (Liam Neeson), Taken

When Liam Neeson was playing telephone with bad guys in 2008’s Taken, he was not just introducing himself to those who had nixed his daughter’s attempt to stalk U2 guitarist The Edge. He was inaugurating a new action hero archetype built of aged wisdom and burrowed brawn, the middle-aged vigilante assassin. (Vigilante applied here because as “one who undertakes law enforcement without legal authority,” while “assassin” fits to associations of precise violent skills.)

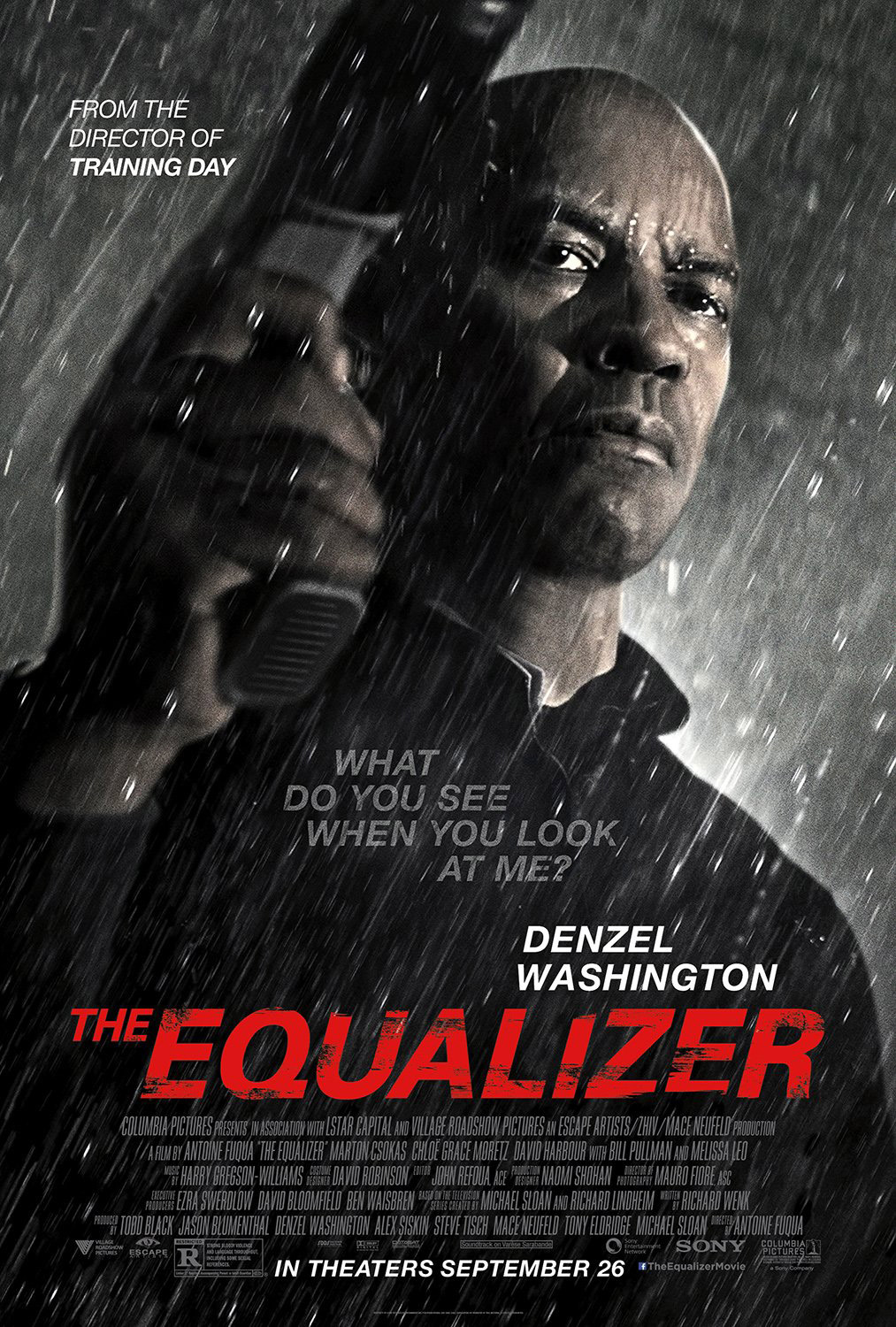

The success of Neeson’s mission as ex-CIA guy Mills, that is, the hundreds of millions of dollars Taken took, confirmed the vitality of a middle-aged vigilante assassin, especially in a burgeoning parallel market of super-powered whippersnappers. In 2012, Tom Cruise would use the archetype to expand himself from his previous Mission: Impossible franchise and to show his dynamo as star but also anonymous former member of the US Army Military Police Corps in Jack Reacher, which caused 52-year-old Cruise to cram author Lee Child’s original character from a towering 6’5” to the actor’s maybe 5’7”. In the past two months, two other middle-aged leading males from action movies of past have taken up the archetype in an attempt to maintain relevancy within the genre: former-James Bond Pierce Brosnan (at the age of 61) became a hard-bargaining ex-CIA agent Peter Devereaux in The November Man, where he acted as both trained killer and conspiracy target, unraveling an international scheme within his former employer. And this week, former Man on Fire Denzel Washington (at the age of 59) takes on Frank McCall, an ordinary late-50s hardware store employee and former-assassin turned freelance vigilante, also known as The Equalizer.

When placing the archetype in action film history, its characteristics, and its popularity in mainstream releases within the last decade or so, we find a predecessor ironically in the work of a thirty-something. In 2002’s The Bourne Identity, Matt Damon’s Jason Bourne character provided a hero who shook up the current action hero criteria, especially in the same year as typical high-flying, X-TREME fare like xXx The Transporter, or Pierce Brosnan’s sad finale with Bond (Die Another Day, which forced Brosnan to surf a tsunami). Here was a disillusioned ex-super-assassin hustling for personal justice, who could outsmart you with a manic level of street smarts, or dismantle you in seconds due to all of his repressed training; audiences didn’t see Bourne when he was a secret agent dealing with super villains. More specifically, Bourne was most of all (at first) trying to evade special forces trying to erase him, while making things right within his own place in the world. Distinctively, Bourne was a product of his environment - post-9/11 government cynicism in flux, reacting against a Patriot Act-era, fear-filled source of injustice more immediate to audiences than megalomaniacs with facial scars trying to blow up the world.

Bourne provided a prototype for this now-archetype that has since added an element of everyman heroism. What was then fortified by a 58-year-old in Taken and continued since is a new type of action hero that establishes prowess with intellectualism and physical force implanted from previous mysterious government training, as expressed by anonymous middle-aged men retired from their business. With these new characters sharing a particular set of similarities, the middle-aged vigilante-assassin can be defined by traits regarding a character’s experience from age, their self-employed heroism in a cynical world, and the means in which former anonymous men of myth exercise their deadly skills to satisfy a personal barometer of justice.

Age is a factor that both grounds and emboldens the middle-aged vigilante assassin. It is used in these films to guarantee an atmosphere of mortality for these characters played by actors who are getting grittier in the face. However, it is shown to be an obstacle that can be overcome, with these characters often facing and defeating foes of a younger age. Youth is something that these actors respond to in these films by encountering it physically as when Cruise faces off against young thugs outside a bar. Or, in the case of Peter Devereaux, youth becomes something which the characters are meant to reflect upon, as Peter tries to influence his apprentice Mason (Luke Bracey), and humble him by exposing the young agent’s naiveté. With the middle-aged vigilante assassin, wisdom is shown to be the most significant result of aging, with their duties following to influence and protect the young people as father figures (something Frank McCall does even when joking around in his civilian clothes). In these facets, the middle-aged vigilante assassin distinctly becomes an intimidating force because of their roles as patriarchs, nonetheless with experience that makes them appear as martyrs who have sacrificed themselves for the safety of the world’s future.

Age is a factor that both grounds and emboldens the middle-aged vigilante assassin. It is used in these films to guarantee an atmosphere of mortality for these characters played by actors who are getting grittier in the face. However, it is shown to be an obstacle that can be overcome, with these characters often facing and defeating foes of a younger age. Youth is something that these actors respond to in these films by encountering it physically as when Cruise faces off against young thugs outside a bar. Or, in the case of Peter Devereaux, youth becomes something which the characters are meant to reflect upon, as Peter tries to influence his apprentice Mason (Luke Bracey), and humble him by exposing the young agent’s naiveté. With the middle-aged vigilante assassin, wisdom is shown to be the most significant result of aging, with their duties following to influence and protect the young people as father figures (something Frank McCall does even when joking around in his civilian clothes). In these facets, the middle-aged vigilante assassin distinctly becomes an intimidating force because of their roles as patriarchs, nonetheless with experience that makes them appear as martyrs who have sacrificed themselves for the safety of the world’s future.

These characters are presented as heroes in a society too cruel for fantasy. (Some could argue that this, not just their lack of razzmatazz, is what makes their films “adult.”) They are self-appointed big dogs in a dog-eat-dog civilization that reflects our own; the realities of which they are embedded are presented with much more immediacy than regular action fare, as they are ingrained with real-life horror. Taken, The November Man, and The Equalizer have their climate influenced by the real-world grotesqueness of prostitution and sex trafficking, of which the films all distinctly feature disturbing imagery of the horrific business. In a similar fashion, Jack Reacher has its plot fueled by a public shooting, and invests time of its story to create real people out of those who have been mercilessly killed. For men like Mills and Devereaux, it provides them with a cause in which a personal motivation of revenge has an added coat of vigilantism. As these horrors are the backdrops for their heroism, these men are anonymous vigilantes in a world defined by its civilian casualties, in a manner that complicates the presence of violence. It darkens the presence of action, touching within audiences a more immediate need for due process.

The idea of violence as instrument for the middle-aged assassin can be framed most succinctly by connecting one of the archetype’s distinct predecessors, Clint Eastwood’s character William Munny in Unforgiven (a revisionist former-assassin project for Eastwood that he acted in while in his early 60s). Like Munny, for vigilante assassins killing is a skill programmed as reflex into their being, a haunting talent used with reluctance, and only when unleashed by a third party. For characters like Jack Reacher and Frank McCall, their skills are used when provoked in physical altercations, often with the title characters offering peaceful ways out from inevitable physical humiliation (Jack tries to warn some punks before he beats them to a pulp outside a bar, and Frank attempts to pay for a girl’s freedom before resulting to his former job.) In this regard, even the vigilante assassin’s passivity becomes a confirmation of power.

However, when Munny’s friend Ned is killed in the middle of a final job in Unforgiven, Munny’s mythical and ruthless skills are unleashed, a la Taken and The November Man, only when the respective male characters have their loved ones ruthlessly put in harm's way. The training is then used for hard-bargaining, with skilled violence providing the only logical means of plowing through impediments to attain a justice that has become personal.

As their own types of retired renegades, going against the grain and on their own, their vigilantism is doled out with unwritten rule. Taking the notion of justice to a level based on mores and the things you just don’t do (like hassle a store owner in The Equalizer, or hit women in Jack Reacher) these men symbolize an autonomous grim reaper’s dolling of what is right and what is wrong. Vigilante assassins like Reacher and McCall live outside the constraints of the law, and even encounter corrupt officials, but are still laboring for headline news justice. (Reacher’s poster tagline: “The law has limits. He does not.”) Physicality is a key force in their delivery of justice, as the similar brutish dealings of men like Devereaux and Mills proves to be the gavel of who is deserving of what fate. (In the case of Taken and The November Man, death is considered proper absolution for atrocities committed.) Dealing out death (as all these men certainly do) can be a common example of how these former government men now live beyond an employee handbook, and beyond a sense of lawfulness itself; they are not vigilantes that badge-wearing law enforcement could ever catch up with.

As their own types of retired renegades, going against the grain and on their own, their vigilantism is doled out with unwritten rule. Taking the notion of justice to a level based on mores and the things you just don’t do (like hassle a store owner in The Equalizer, or hit women in Jack Reacher) these men symbolize an autonomous grim reaper’s dolling of what is right and what is wrong. Vigilante assassins like Reacher and McCall live outside the constraints of the law, and even encounter corrupt officials, but are still laboring for headline news justice. (Reacher’s poster tagline: “The law has limits. He does not.”) Physicality is a key force in their delivery of justice, as the similar brutish dealings of men like Devereaux and Mills proves to be the gavel of who is deserving of what fate. (In the case of Taken and The November Man, death is considered proper absolution for atrocities committed.) Dealing out death (as all these men certainly do) can be a common example of how these former government men now live beyond an employee handbook, and beyond a sense of lawfulness itself; they are not vigilantes that badge-wearing law enforcement could ever catch up with.

In spite of such a mythological existence, often asked “who are you?” by incredulous ne’er-do-wells, these vigilante assassins embed themselves in plain sight. These are men who are originally presented as wanting to be left alone with the blood on their hands. For their characters, it is a remark about the control over their life situation, that they can eat out in the open and are protected by their sharp skills, a mix of street smarts and top-secret government training. Bryan is just a dorky dad who makes measly money as a bodyguard for a pop star, Jack’s element of mystery is arguably most of all from the notion that he can’t be found via cell phone because he refuses to get one, Peter retires from the CIA and owns a quaint coffee shop in Europe, and Frank just sits at the same diner every night after working during the day at a home department store. In terms of an actor choosing this archetype, this trait can be seen as a reflection of heroes identifying with a wider audience by relating to their anonymity. Similarly, this boasts a notion that proves the vigilante assassin is bigger than a disguise, and that their superpowers are from hard-won intelligence.

The middle-aged vigilante assassin is moving in full force within the action genre. A third Taken film is due out in 2015, and The Equalizer opens tomorrow after reportedly giving Sony its best test screening scores ever for an R-rated film. The momentum of these projects is likely to keep other characters like Jack Reacher and Peter “The November Man” Devereaux in the business, as both of those financially underwhelming first projects have sequels being kicked around.

In the next few months, through new projects this archetype will evolve, but nonetheless fulfilled by actors old enough to bear its power. In John Wick, an actioner that played well recently at Fantastic Fest, a 50-year-old Keanu Reeves as former hit man responds with his particular set of skills to Russian mobsters who killed his dog. Later in early 2015, a 54-year-old Sean Penn will use Taken director Pierre Morel to assume status as middle-aged action star with The Gunman, whose plot synopsis from Cannes Film Festival 2014 indicates Penn will be playing a “former Special Forces soldier” who must go on the run. And of course, god of the archetype Neeson will pick up the role yet again (with the characteristics echoed in his projects like Non-Stop and even A Walk Among the Tombstones) for the slightly different April 2015 film Run All Night, in which he plays an “an aging hit man” forced to battle a brutal former employer.

In the next few months, through new projects this archetype will evolve, but nonetheless fulfilled by actors old enough to bear its power. In John Wick, an actioner that played well recently at Fantastic Fest, a 50-year-old Keanu Reeves as former hit man responds with his particular set of skills to Russian mobsters who killed his dog. Later in early 2015, a 54-year-old Sean Penn will use Taken director Pierre Morel to assume status as middle-aged action star with The Gunman, whose plot synopsis from Cannes Film Festival 2014 indicates Penn will be playing a “former Special Forces soldier” who must go on the run. And of course, god of the archetype Neeson will pick up the role yet again (with the characteristics echoed in his projects like Non-Stop and even A Walk Among the Tombstones) for the slightly different April 2015 film Run All Night, in which he plays an “an aging hit man” forced to battle a brutal former employer.

While the means of a character's experience may slightly change for films like John Wick and Run All Night, the intrigue for audiences remains the same - the guarantee that leading actors whose middle-age reflects delicate mortality will provide viewers (young and old) flesh-and-blood cinematic patriarchs who uphold the rights of the everyman, through extraordinary physical and intellectual skills earned strictly by age and experience. For actors, the profitable and in-demand gig offers a gritty reboot to their image, while also presenting them as an unstoppable force; the middle-aged vigilante assassin equips fixtures like Liam Neeson and Denzel Washington with what seems to matter most in youth-obsessed Hollywood - to appear authoritative, and to be franchised.