The one thing I took away from reading "Tuck Everlasting" in middle school is that living forever would suck. Not simply because I hate moving and would get tired of it after a thousand years, but because death is an essential aspect to the gravity of life. An end, or even just a tiny sense that there may be an end, gives existence its shape.

The one thing I took away from reading "Tuck Everlasting" in middle school is that living forever would suck. Not simply because I hate moving and would get tired of it after a thousand years, but because death is an essential aspect to the gravity of life. An end, or even just a tiny sense that there may be an end, gives existence its shape.

- READ Nick Allen's Scorecard Review of "The Wolverine"

- READ Jeff Bayer's TOP 7 Moments from Hugh Jackman's Wolverine

The new Wolverine posits a compelling quandary with its indestructible title hero, especially after the haze of the most recent San Diego Comic Con (#SDCC) event. As stated by Yashida to Wolverine when offering to take the comic book character's mortality, "eternity can be a curse." He is right. Eternity is a curse for Wolverine in the movie so much as it is his existence as a fictional character. The idea of living for eternity essentially renders him inconsequential mush. He floats in an Alaskan limbo with a life that has no meaning, or as a comic book character with only so much he can provide as entertainment before living a challenge-less existence that marks his significance as a hero with obstacles to overcome as null and void.

It is no coincidence that the film's best ideas concern the challenge of Wolverine's immortal characteristics, especially when the plot has villain Viper taking away his instant healing powers. In these moments, it is not only just the concept that Wolverine will be inconvenienced by a shotgun blast to the chest, but that he will suffer sustained pain from various afflictions, and said bullet wounds will impede on his ultimate hero goal of trying to save others. The immortality aspect has taken a step to the side for the sake of highlighting Wolverine's very reason to exist. This scenario also provides a much livelier sense of urgency to the goal of this particular hero as opposed to his simpler actions, which more often than not concern the curiosity of whether he'll be able to shake off his latest face scrape before yet another one comes in his direction.

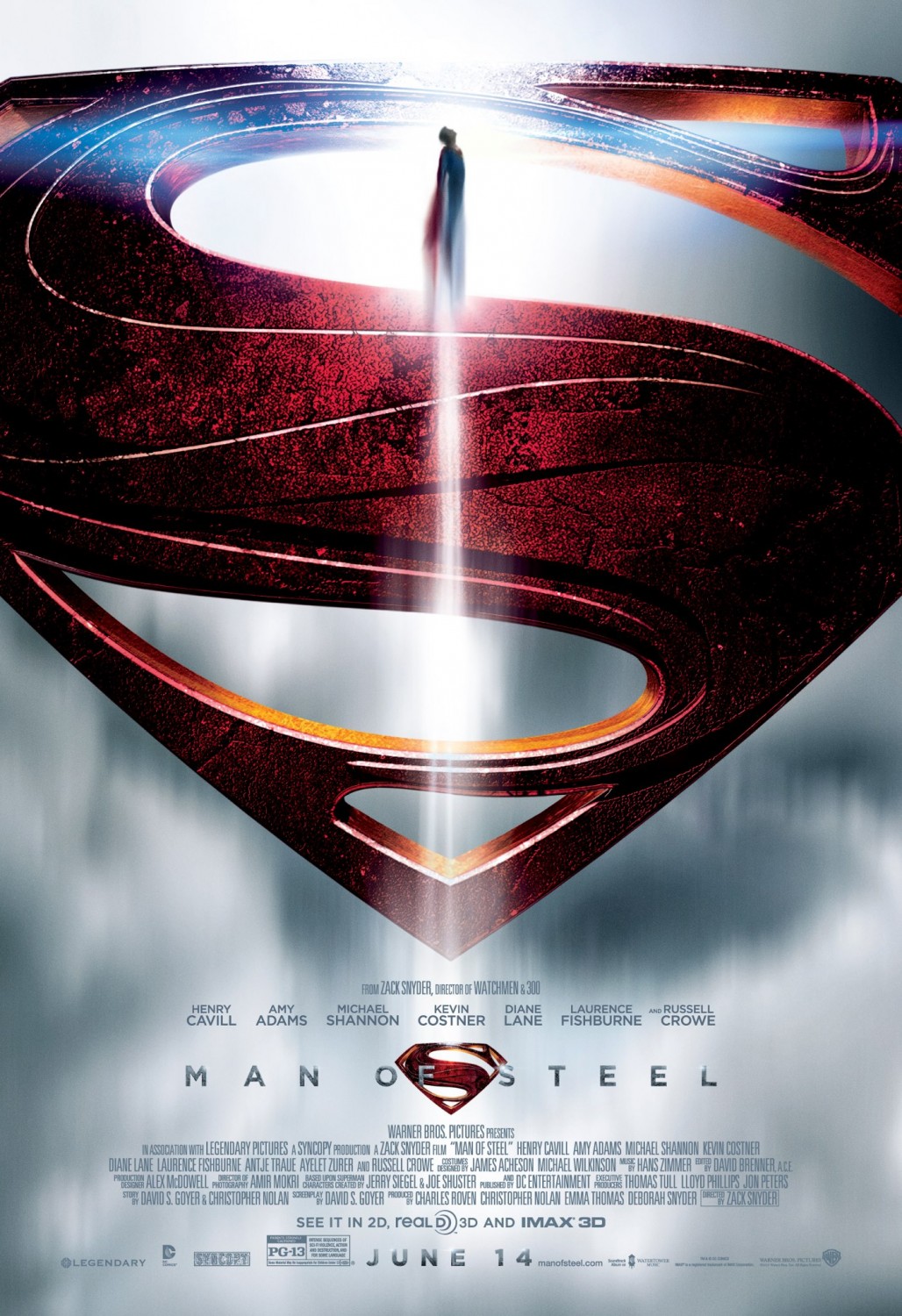

After experiencing the numbing Man of Steel and later watching The Wolverine after all that #SDCC news, I could feel that this nagging dilemma of eternity with more obviousness than usual. With more heroes and their progressively huger projects, reading the news felt like warnings of eventual super servings of thrill-less gruel, from both cinematic universes of DC Comics and Marvel. The mystery that makes genre storytelling exciting, the gamble of a hero's ability to fight another day, seemed to be more absent than usual with these projects.

As far as I can tell from watching every massive movie Marvel has made since the first Iron Man, the comic empire does not seem interested in creating a definitive character arc with its tent-pole figures, and then one day leaving said arc alone. Their comics obviously respect certain stories, and have conclusive arcs, but their films do not have that promise. The Marvel cinematic universe seems interested in pushing things toward the wrong direction, populating us with characters who do not have shape, or a strong sense of life-or-death urgency, but only more sequels. Watching a Marvel film does not come with the same fear of consequence as other action movies. None of them strike me as vulnerable, despite most of them having human conditions. They too readily represent as a group the curse of immortality bestowed on literary characters, who only have to answer to capitalism in terms of whether they shall live or die within the fanbase population's perspective or not.

DC Comics are certainly not excused from this accusation either. With their announcement of the next Man of Steel movie to feature Batman, this leaves one very worrisome in general. DC Comics' nervous plan to try to become Marvel by bundling up its franchises is going to make for extremely and painfully inconsequential entertainment. If this Freddy vs. Jason-esque new movie is in fact called "Batman vs. Superman" or vice versa or anything with versus in it, then we are doomed to watch the Rocky and Apollo Creed freeze frame all over again, a frozen moment that has no clear winner because it doesn't matter ultimately who wins. Will DC Comics kill off Superman in a second Man of Steel movie? No. Will they bring Batman back into the multiplex game just to make him bite the proverbial dust? Also no, though that would be incredible if such were to happen. Did you think that the climax fight scene in Man of Steel between Superman and General Zod was hugely boring because it was just two gods playing rough house against a city skyline? Imagine the excitement, then in which gods even more powerful than that, those of billion dollar franchise entities, are supposedly facing each other in a hundred million dollar duel with no immediacy to their existence. A "versus" movie would be more interesting if they debated cape length as opposed to physically scuffling.

DC Comics are certainly not excused from this accusation either. With their announcement of the next Man of Steel movie to feature Batman, this leaves one very worrisome in general. DC Comics' nervous plan to try to become Marvel by bundling up its franchises is going to make for extremely and painfully inconsequential entertainment. If this Freddy vs. Jason-esque new movie is in fact called "Batman vs. Superman" or vice versa or anything with versus in it, then we are doomed to watch the Rocky and Apollo Creed freeze frame all over again, a frozen moment that has no clear winner because it doesn't matter ultimately who wins. Will DC Comics kill off Superman in a second Man of Steel movie? No. Will they bring Batman back into the multiplex game just to make him bite the proverbial dust? Also no, though that would be incredible if such were to happen. Did you think that the climax fight scene in Man of Steel between Superman and General Zod was hugely boring because it was just two gods playing rough house against a city skyline? Imagine the excitement, then in which gods even more powerful than that, those of billion dollar franchise entities, are supposedly facing each other in a hundred million dollar duel with no immediacy to their existence. A "versus" movie would be more interesting if they debated cape length as opposed to physically scuffling.

The disappointment for this announcement also comes in the face of DC Comics' previous heroic work to encourage the notion of mortality with Christopher Nolan's Dark Knight trilogy, respecting the space of a tentpole character's arc, and letting it be so that it could ultimately find its shape. There is a reason that these three Batman films are so resonant, and feel to be more embedded in a stronger sense that is reality than a Marvel film. It is that Nolan set himself out to create an arc, and then leave it alone. It does not matter whether Batman lives or dies in the end, or that he may have passed on the Bat Cave to Joseph Gordon Levitt's character in the third film's final shot, it only matters that the trilogy has a finale. Of course, Batman will find another reincarnation as he always will, but Nolan's version of this Batman is born in Batman Begins, and then passes on in The Dark Knight Rises. As there is a thrill in watching a hero dance with death in any movie, so is the thrill in witnessing a story reach its final destination, a death-like point of peace, and completing its objective of trying to be a complete plot.

As we are cinematically introduced to more of these characters, it is important in storytelling that fictional characters, especially ones that are considered to be immortal, are still presented from the perspective of what makes them vulnerable. In this regard, it is imperative that we also are at least presented the illusion that they are not guaranteed, and could be destroyed. These moments, especially the more believable that they are to a film's own standards, are where the characters find their purpose. As every hero needs a good villain, so does every hero need their weaknesses and obstacles as much as their strengths. This is how even the most supposedly immortal of characters can feel alive as fictional beings, regardless of what super strengths or resilience they may have. It is the difference between the thrill of watching John McClane in Die Hard, and just letting him do his over-the-top thing in A Good Day to Die Hard.

As much as we may love these characters, we need a sense of their boundaries to fully embrace them and what they are created to provide us as fictional characters, as meant to excite our sense of entertainment. To prevent from being personality mush that fails the entire purpose of being a fictional character, these literary beings need to have limits, and this ever-evolving list of cinematic storytellers need to start embracing those limits.

For a comic book hero, immortality should be considered an illusion as best, especially as fictional characters of entertainment are meant to overcome obstacles that stand as immediate challenges and definitions of their very existence. The promise of living forever is what makes them the least interesting as characters, as all comic book characters are already immortal thanks to their existence as creations of literature. Wolverine may be filled with Adamantium, but he is no more immortal than Charlie Brown, or a billion other creations floating around in the great creative unknown as franchise deities.

With this constant movie marquee pig pile of characters meant to fight the evil we can not, the very reason for comic book heroes to exist feels in jeopardy. A key reason that these films are beginning to feel tiresome is that they consistently stand as examples of overzealous visits to the fountain of youth. The characters are becoming more obscure, their numbers are multiplying, but they are all starting to blend into the state of inconsequential mush that Wolverine is at least excitingly liberated from in this new film.

Whereas, it is a whole lot more exciting to experience and witness life when you know an end is indeed coming, and that nothing is guaranteed. A character's eternity is a curse indeed, and not just for themselves — for their audience as well.