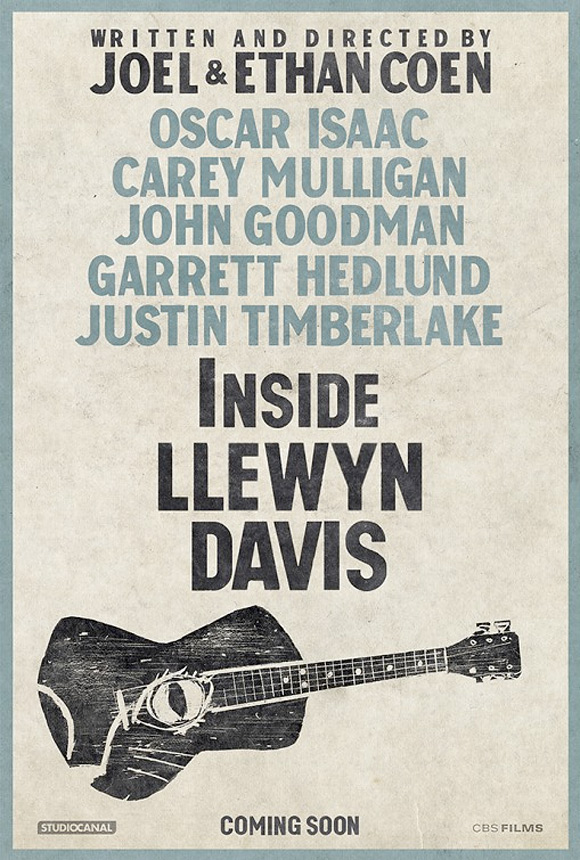

A folk movie in the key of Coen, Inside Llewyn Davis is a drama about a folk singer named Llewyn (played by Oscar Isaac) who seeks direction after the death of his musical partner Mike. Blown by the same winds of fate and/or bad luck as seen in the previous Coen film A Serious Man, Llewyn journeys in and out of the lives of various characters (played by Carey Mulligan, Justin Timberlake, John Goodman, and F. Murray Abraham among others) with a nameless cat in tow. Set in a pre-Bob Dylan 1961 New York City, the film features numerous scenes of musical performance from Isaac, with the Coen Brothers using famous folk songs to further enrich their narrative about mortality, loosely inspired by the life of Dave Van Ronk.

Though Isaac has appeared in numerous films like Drive, Sucker Punch, Robin Hood and 10 Years, this is the former Juilliard grad's first lead role. He has upcoming appearances in films from writers like Alex Garland, William Monahan, and Hossein Amini.

A folk movie in the key of Coen, Inside Llewyn Davis is a drama about a folk singer named Llewyn (played by Oscar Isaac) who seeks direction after the death of his musical partner Mike. Blown by the same winds of fate and/or bad luck as seen in the previous Coen film A Serious Man, Llewyn journeys in and out of the lives of various characters (played by Carey Mulligan, Justin Timberlake, John Goodman, and F. Murray Abraham among others) with a nameless cat in tow. Set in a pre-Bob Dylan 1961 New York City, the film features numerous scenes of musical performance from Isaac, with the Coen Brothers using famous folk songs to further enrich their narrative about mortality, loosely inspired by the life of Dave Van Ronk.

Though Isaac has appeared in numerous films like Drive, Sucker Punch, Robin Hood and 10 Years, this is the former Juilliard grad's first lead role. He has upcoming appearances in films from writers like Alex Garland, William Monahan, and Hossein Amini.

I sat down with Isaac in a roundtable interview to discuss his film, the symptoms of paranoia in being an actor, how he matched the expressions of a cat, and more.

Inside Llewyn Davis opened in Chicago on December 20.

While this movie does have inspiration from the story of Dave Van Ronk, it is not like 'Inside Llewyn Davis' is a direct biopic of his life, but an artistic interpretation. What do you think can be gained by expressing a life story more artistically than literally?

You're shackled less to historical accuracy, I guess, within this person's life. Obviously when I walked in the room, [the Coen Brothers] had to think for about a month about me, but I'm a not a 6' 3" 300 pound Swede. I don't sing the way he sang, but I never tried to do any of those things, even though I did read "The Mayor of McDougal Street" and I did learn how to play Dave Van Ronk's repertoire. I also watched videos of him to capture at least the type of person he was, the essence of someone who wasn't trying to reinvent himself; he was very direct about who he was. He's a guy from the boroughs, he's not inventing a story about how he made it, and that was very important. And [Inside Llewyn Davis] turned into something else when they cast me, there were a couple lines about howling, and I don't do that, but I could have. And when I showed up to T-Bone's place I thought I would be surrounded by experts, and they would teach me how to get this one sound, but none of that ever happened. I was never told how to sing or how to play, I just took the lead on that to get the audition. I said I was going to try to sing like me, but with Dave Van Ronk songs, and I just kind of went with that.

How do you perform a Coen comedic moment most effectively? Do you play it straight?

Whenever I would fake a comedic turn, it wouldn't totally work. But whenever I played with the absolute most amount of pain, is when [the Coen Brothers] would laugh the most. When I was feeling the most desperate, and at my breaking point, is when they would cackle.

In 'Inside Llewyn Davis,' Llewyn's sister makes a point about not understanding the entertainment business because she lives in the normal world. While that was a statement to have been said in the film's setting of 1961, do you think that even in 2013 there is a distance between what the public understands about the entertainment business?

Yeah. There is a luxury in it, that's why it may seem so glamorous, but it's also a real slog as well. It's funny, when I started off, actors can be pretty neurotic. It's clear where that comes from; paranoia is when you think people are talking behind your back, but as actors we know people are talking behind our back. We go into a room and we leave, and they're talking about us. It's like a Petri dish for neuroses.

A lot of your upcoming projects, like Alex Garland's 'Ex Machina,' Hossein Amini's 'The Two Faces of January' and William Monahan's 'Mojave' are screenplays by writer/director filmmakers. Do you think there is a particular advantage to working with someone who takes over both the writing and the directing?

That is really great, because there is a bit more control over the tone. You make a movie three times, script, production, editing. But a lot of those guys are first-time directors. The script, that's my first interface with this possible job. When I read a script and it seems like it can keep my interest for the duration of shooting, that's how I pick a job. Is there enough there that I can remain curious about it, and investigating it the entire length that it takes to shoot the film? Because if three weeks in I check out, that'd be death. It starts with a script, although now, that I've had experience with a lot of first-time directors, you see the value of a really great director. Because you try a lot of shit, you try stuff, and you're in the hands of someone who is the one who is watching, and making sure that the tone is right and fitting into the greater theme of the movie, and also its providing context for your character. So you could be doing the best work of your life and if someone doesn't know how to shoot it or how to use the right take, or how to set the take up with the right scene before or after, then it's pointless. So I am definitely interested in working with strong directors.

'Inside Llewyn Davis' required some extensive scenes of you working opposite a cat. Does that require a lot of takes, or just more improvisation than usual?

Well, we had like four different cats, because you can't train a cat.

How about the shot in which you two match glances when sitting in the passenger seat in the car to Chicago?

That was a more sedated cat, but not because of us. And I would just watch out of the corner of my eye, and I would hold it and feel him start to go, and then I would go. And then I would hold it, and see the cat from my peripheral. As soon as I did it, I could hear everybody laughing behind the camera.