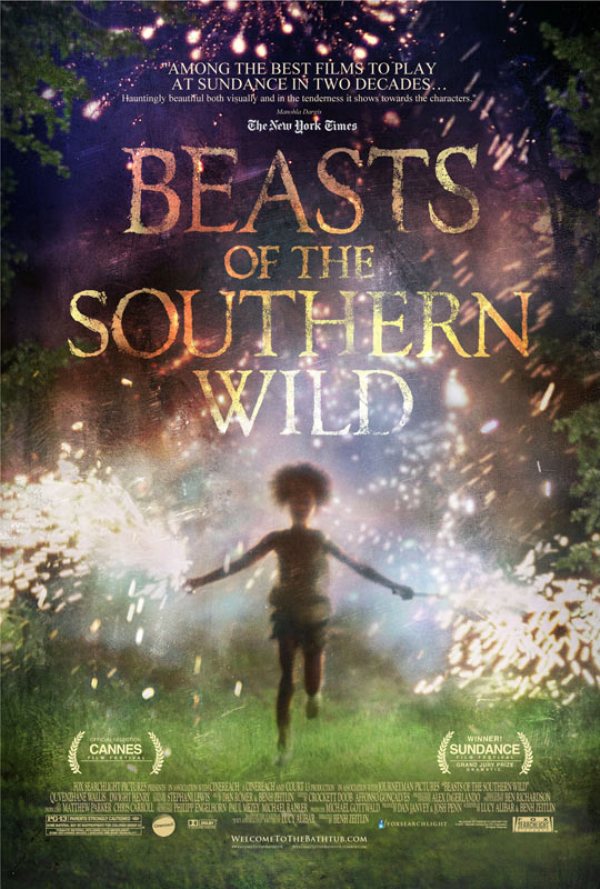

One of this film year's biggest discoveries has been Beasts of the Southern Wild, starring first-time actors Quvenzhané Wallis and Dwight Henry, as directed by first time helmer Benh Zeitlin. The aesthetic-driven indie film is about a father (Henry) and his young daughter (Wallis) who refuse to leave their hurricane-effected land near New Orleans called The Bathtub.

Though captured by a camera spiritually embedded into the unique territory, Zeitlin is originally from Connecticut. The 29-year-old studied film at Wesleyan University, which also has alumni like Avengers director Joss Whedon and blockbuster guy Michael Bay.

One of this film year's biggest discoveries has been Beasts of the Southern Wild, starring first-time actors Quvenzhané Wallis and Dwight Henry, as directed by first time helmer Benh Zeitlin. The aesthetic-driven indie film is about a father (Henry) and his young daughter (Wallis) who refuse to leave their hurricane-effected land near New Orleans called The Bathtub.

Though captured by a camera spiritually embedded into the unique territory, Zeitlin is originally from Connecticut. The 29-year-old studied film at Wesleyan University, which also has alumni like Avengers director Joss Whedon and blockbuster guy Michael Bay.

I sat down with Zeitlin in a roundtable interview to discuss the crafting of this film, his co-written score, and the key to getting an eight-year-old to act without turning her into a puppet.

Beasts of the Southern Wild opens in Chicago on July 6.

Before the final product was taken to the Sundance Film Festival, this movie was worked on in the Sundance Film Lab, famous for assisting first-time directors like Paul Thomas Anderson and Quentin Tarantino with their feature debuts. What kind of work did your film receive in the lab?

We came there with the rawest first draft. I had no attachment to it, I wrote it in two weeks. It was just a pack of ideas. I wasn't sure what the film was about. The lab is like an emotional boot camp, where they are forcing you to explain every choice that you made. Any line in your script, any shot, you have to explain how that is connected to what you want to say, and how what you want to say is connected to who you are, and figuring out where that comes from. It is rough questions, and you are revealed to be a liar and a phony over and over again. But eventually, through that brutality, you find that core that was the reason you started writing it, and you start disciplining your choices based on that.

The lab really found what the film was about, this experience of "How do you emotionally survive losing the things that made you?" I had a scene where a cow flies through someone's roof. I loved that scene, but we couldn't find any connection of it to the heart of the story. [The lab] gets you grounded, and gives you a framework to make choices.

What kind of cinematic influences did you have with this film?

I tried not to watch a ton of fiction around this. I was largely inspired by documentaries, and by the place itself. I think there is probably a connection of people in the South here. There is a lot of extrapolating of things from the world, and patching them together in the easy way that they are not in the world. It's one of the further way it plays from Louisiana, the more that is seen in the context about something magical in the area. Whenever we show the movie down there, people say, "That's how it is." But it's very recognizable stuff that's in the movie, and it all comes from driving around south Louisiana.

As a person from New York, what was the first thing that knocked you out about New Orleans?

I had been there a couple of times. I went there as a kid, and was very haunted by it. It was something that I talked about. I grew up a Tom Waits person. There's something that resonates in the city that's so visceral. There's this darkness and joyousness mixed together at all times. I don't know if I became like that before or after I was there, but when I came back from it there was this natal feeling of, "This is where I come from" in an abstract way. I think for people who come as outsiders, it is like walking into a book you love. It feels like a heightened reality. But when I went there, I didn't intend on staying, but I did. It had to do with the production of my first live-action short. A guy came up to us when we were were doing casting, and he had all of this random stuff he had collected, and said to us, "Well, I heard you were making a movie." It was just like my film - a story I had written had reflected upon my life. It felt like something I needed to follow.

Could you talk about shooting this movie on film as opposed to digital?

First of all, I'm a sentimental bastard. I made my first film, Egg, on a 16mm and cut it on a flatbed. There's something magical about a series of still picture coming one after the other, and there's a little bit of magic lost when digital turns it into this other thing. The grittiness of the image fits with The Bathtub. Bathtub is a place with no technology. It emerges much more naturally from her world because film is organic. To get good photography in the locations we were going, [film] was also the easiest and cheapest way to do it. We were on tight little john boats, and there was no way for us to be data managing, and there's no power.

Along with co-writing and directing, you also helped write the score for the film. Is that something you'd like to keep doing with future projects?

Definitely. I do a lot of things on the movie, I also collaborate on all those things, but I don't think of them as separate. I could not imagine directing something I didn't write, or not scoring something I didn't direct. The processes are so intertwined. Did the music come before or after?

After, on this one. Normally it comes before. It's the idea, and then the music emerges simultaneously. It was the process of figuring out the perspective of the music. The stuff that I wrote during the movie didn't have the right perspective because it wasn't coming out of [Hushpuppy's] consciousness. It all became, "What is her sense of her own story?"

Did you ever study film scoring? No. Self-taught. I was in a band in high school. The score is really pop music masquerading as film score. They are all song-based. My co-writer, he comes from the pop world too. How much of this movie takes place in Hushpuppy's consciousness? The whole movie. But I remember torturing for a long time over the questions that are left open in the film, and that evolved. At a certain point, I stopped thinking about the answers from an adult point of view. The film is her film. It is something that respected her reality. If she believes it is real, it is real because it is her movie.

What was it that struck you about Quvenzhané when you auditioned her?

It was the first call-back; she was defiant towards me. That was really important. It is easy to puppeteer a kid. She was totally refusing to do this thing I was asking her to do, because she didn't think it was right. She was the youngest person we saw. She came in, and I was trying to get her to throw something at the other actor. She told me it wasn't right to throw something at someone you didn't know. This girl had her own style, her own sense of morality, her own world views. That's what I looked for in every actor.

Working with child actors is hard. What is your perspective on trying to get them to work on set?

You've got to play a lot. I worked with her like an actor, even more so than other actors. It wasn't about tricks or smoke and mirrors. We really talked about scenes. Movie sets are stressful, and high pressure environments. Children don't respond well to that. It doesn't feel like a game. It makes them uncomfortable, and they don't use their own personality. A lot of work was done to play in the shoot. I would set up these shots, completely ready to shoot, and then bring her in. We would throw water bottles back and forth, let her mess up my hair, and then right when we were having the most fun, I would say "action."