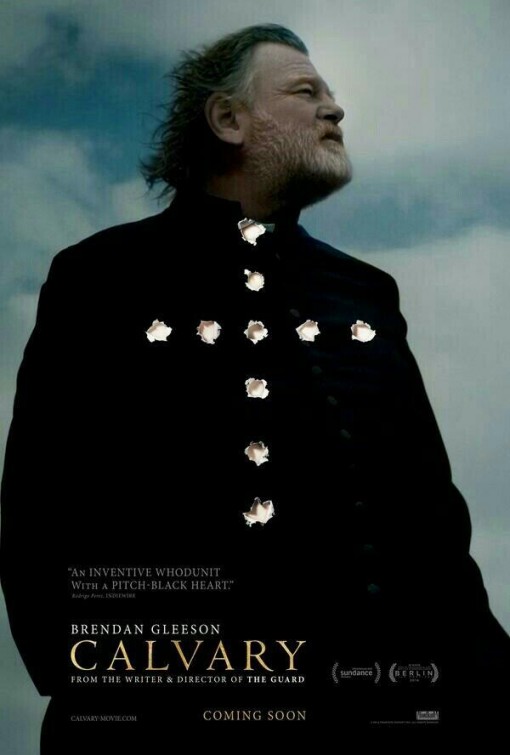

Calvary

Calvary Directed by: John Michael McDonagh Cast: Brendan Gleeson, Chris O'Dowd, Kelly Reilly, Aiden Gillen Running Time: 1 hr 40 mins Rating: R Release Date: August 8, 2014 (Chicago)

Calvary Directed by: John Michael McDonagh Cast: Brendan Gleeson, Chris O'Dowd, Kelly Reilly, Aiden Gillen Running Time: 1 hr 40 mins Rating: R Release Date: August 8, 2014 (Chicago)

PLOT: A priest of a small town (Gleeson) has a week to live after being threatened by a random man during confession.

WHO'S IT FOR? Those who like dialogue-based films where the energy is in the ideas, and even its editing.

OVERALL

In Christopher Guest’s 1989 satire The Big Picture, Kevin Bacon plays Nick Chapman, nubile filmmaker who dreams of splashing into the world of directing by creating a rapturous black and white tome on life and death a la Ingmar Bergman for his first feature. Cherry-picked right from film school after making a hot short film, he attempts to create this supposed opus before the rest of The Big Picture’s narrative takes hold, in which Bacon loses creative control of his project (his version of Autumn Sonata eventually turns into a sexy bikini beach comedy). The Big Picture parodies the dreams one have when trying to get into the tumultuous moviemaking business, but it does provide one caveat, that Bacon was trying to make a film outside of his wisdom, and may possibly have been saved from embarrassing himself by expressing questions that he has no idea how to ask.

After being discovered with his first feature The Guard, writer/director John Michael McDonagh attempts to go down somewhat the same path, taking a sobering jaunt into the question of faith - a distinctly shift of speed compared to that first film, which featured more direct dry comedy and a slamming N.E.R.D.-scored title sequence, along with scenes of shootouts, etc. Despite the blatant imperfections within his now second film Calvary, McDonagh’s storytelling ambitions succeed for the reason that Bacon’s fictional ones did not in The Big Picture - Calvary is a film made on McDonagh’s terms, through his voice, and it comes with a down-to-earth conversational sense of wisdom.

Calvary is a drama that frames an everyman faith as fear of death. It takes place in the same densely populated Irish lands as The Guard, with characters who are laboriously colored to the same degree. Brendan Gleeson plays Father James, a good-natured priest who is threatened by a man formerly while doing confession in the film’s first scene; the mysterious man says that he will kill Father James in a week, as a type of black comic revenge for the abuse that he suffered from other men of the priesthood.

After deciding to respect his vow of confessional secrecy despite the threat made on his life, Calvary follows Gleeson as he interacts with the members of the small town in which his small church is located; many of them members of his tiny parish. The issues of these morbid characters are not related to faith, but to their own behaviors that are spurred from their lack of connection to religion, or a guilt to God. A sampling: one woman is having an open affair, but also has a mysterious bruise on her face; another man wants to a pistol of which to commit suicide with; in one of the film’s less successful passages, a psychopath taunts the idea of forgiveness and refuses to say where he buried some bodies; a rich man with a criminal past challenges the notion of forgiveness by trying to buy it.

When interacting with Gleeson, they often face him with unamused apprehension, or an aggressive playfulness; they try to screw around with him as if messing with the priest were a way of spiting God, or the guidelines within faith. Calvary is also specifically placed in a time after unearthed sexual abuse within the church, which has made the concept of being a priest a joke to many people, and an even difficult calling for those trying to earnestly pursue it. In a means that satisfies Calvary with colorful interactions and intriguing moments that transcend the drab atmosphere and color, Gleeson meets them toe-to-toe with his sarcastic wit, as he analyzes them and tries to be a good man in a morally rough village.

McDonagh’s aspirations are legitimized by a strong supporting cast (Aiden Gillen's deliciously weird Dr. Frank Harte in particular) but especially by the anchoring performance of Gleeson, who provides this movie with much of the crucial concepts to its tone; its sarcasm, its stillness, its conflict, its stalwart vulnerability. Interacting with the members of his small town, Gleeson carries a muted distress, creating a dimensional character whose answers to others can come with his own self-questioning. Gleeson and McDonagh distinctively create a priest who is flesh-and-blood with different vices, but who takes his job as a means for community mentor most of all. Curiously, and something that speaks about his character, Gleeson does not often interact with the conflicted people of his town through scripture.

While tackling the beast of faith in broader strokes, and more as a question about morality, McDonagh confidently contains this story with its sets of interactions. He has created an intriguing idea of a man of faith, and the intrigue in Calvary is not in seeing a priest's time begin to wind down, but to see him meet with other people who have their own grievances. Calvary shows McDonagh's strength in conversation, with the dialogue between two characters the only life source that the script needs. To keep a certain intensity to this movie’s atmosphere despite its subtle spectacle, McDonagh bookends these interactions with aggressive transitions, and cuts aggressively between characters. Accompanied by potentially sappy choral moans, landscape shots show the barren beauty of the Irish terrain.

Calvary also expresses the comfort that remains to be grown within McDonagh and his screenwriting craft, with consideration to some of its imperfect moments. He has the same problem as his brother Martin regarding characters viewing themselves as script beings, not human beings (as Martin showed in his underwhelming Seven Psychopaths). With Calvary, John Michael McDonagh finds a controversial crutch in letting the characters talk about themselves like they are types, as if they’re all storytellers. Similarly, he is fine making a very literal connection within Gleeson, who has parallel responsibilities in the film both as a Father, and father to his daughter played by Kelly Reilly (whose angelic red hair is the brightest color to be seen in this film, aside from a hellish fire).

With this film setup so strongly, McDonagh doesn’t end the film with a steady payoff; it is more memorable for its faulty choices than a sturdy conclusion. A montage that bonds all of Gleeson’s characters together in one shot is handled too obviously, an idea that is at least better executed when we are introduced to many of these characters by seeing them take communion from Gleeson at the beginning of the movie.

Then there are the shots to be found in between the closing credits of the previously empty landscapes, now without people in them at all. Instead of being a profound statement, it expresses most poignantly of all that McDonagh has seen and remembers L’Eclisse, which famously does the same thing of showing the previous locations shared by two lovers.

In the way that Boyhood theorizes that the big question of life can be answered with “we’re all just wingin’ it,” Calvary doesn’t go for the huger questions, but it still aptly explores the conflicts of faith and morality that are a basic part of human coexistence. McDonagh knows that he doesn’t have the wherewithal to ask the big questions, or to make a film that echoes throughout the debate within religion. After a few more movies, maybe.

FINAL SCORE: 7/10