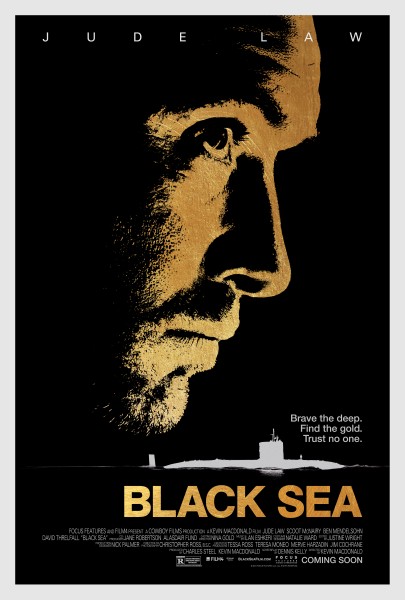

'Black Sea' Interview with Director Kevin Macdonald

Director Kevin Macdonald's Black Sea an is a sturdy old-fashioned thriller, an adventure and treasure hunt set within the confines of a submarine. its captain is played by a burly Jude Law, who leads a group of ruffians down to the bottom of the Black Sea to find a sunken Nazi sub that is rumored to have tons and tons of gold on board. With the drama of the film ratcheted up with crew tension and water conditions, Macdonald's film is a tense throwback, albeit a parable about the 99% helping each other since they're on the same boat.

Director Kevin Macdonald's Black Sea an is a sturdy old-fashioned thriller, an adventure and treasure hunt set within the confines of a submarine. its captain is played by a burly Jude Law, who leads a group of ruffians down to the bottom of the Black Sea to find a sunken Nazi sub that is rumored to have tons and tons of gold on board. With the drama of the film ratcheted up with crew tension and water conditions, Macdonald's film is a tense throwback, albeit a parable about the 99% helping each other since they're on the same boat.

Macdonald previously directed films like How I Live Now, The Last King of Scotland, The Eagle, and Touching the Void. He was also the filmmaker chosen to compile a worldwide stack of footage for the documentary endeavor Life in a Day.

I sat with Macdonald in a roundtable interview to discuss the making of the film, it's non-noble cause, and the things you learn about filmmaking when shooting inside a submarine.

Black Sea opens in Chicago on January 30.

'Black Sea' arrives at an unusual time in which our western attitudes towards Russia have changed in the past year.

There’s a little oddity about this film is that the place that they go to pick up the submarine is Sevastopol, which is the main town in the Crimea, and has since been taken over since we shot the film by the Russians. There was quite a lot of sensitivity about that. You’ve got this guy who is a Ukranian admiral, and we had a little scene where he talked about being Ukrainian rather than Russian, but we cut it out not because of the politics but because it slowed things up a bit. Now the Ukrainians don’t even have a navy, because the Russians took everything. One way that it did directly affect us is that we were going to back and shoot the real vintage submarine that we used for interiors in England, that the Ukrainians had and put cameras on it, but we couldn’t go back because the invasion happened and the Ukrainian navy ceased to exist.

This film was actually bought by a distributor for Russia and the Ukraine, who is a Ukrainian distributor. And they’re like the biggest independent distributor in Ukrainian and Russia called Top Film, and all the staff we were working with were Ukrainian, and they came up to release the film in Moscow, several times with journalists you could see arguments developing.

How did you go about tackling these characters?

I didn’t see the Russians as being any worse than the Brits. I felt like it’s more that they are the same, they have more in common than they don’t have in common, because they’ve been sailors their whole lives. But also because they’ve been thrown on the scrap heap. It’s more about working men with blue collar skills whose skills are no longer needed or wanted, and they’re thrown away. And it comes down to the 99% versus the 1%, where so many people are being exploited and there’s a few that are making out like bandits. What drives this heist is not that they want to get rich, it’s the “I want to get back to the bankers who made us lose our respect.”

’Black Sea’ has the interesting angle as a story without any clear protagonist. What intrigued about this story where we’re stuck with these characters who are without any noble cause, and just want to make money?

What’s interests me is that they are as characters they are very flawed because they have been warped by their anger at the system in a way. And I suppose in a simple way, if the film is about anything in the end, it’s about that in the end instead of getting rich or not having respect, what Jude’s character has done, he should have paid attention to his family, or been a good dad, or whatever. Actually, that’s why we didn’t want to have the evil corporation be sort of personified. It’s not about the corporation, it’s about the individuals on the submarine and what it does to them, and that does to them, and that sense of greed, and that wanting to get that self-respect back. I suppose the system makes us all feel that the only way we can get respect is being rich, because those are the only people that society deems of value, so, “We’re gonna get rich, we’re gonna get that respect,” but they have to realize that is not necessarily truthful, or useful.

How did shooting in such tight spaces reflect in the filmmaking? Did you have a particularly small crew?

The crew was not big, in fact it wasn’t a very big expensive movie. We had to cut our cloth in many respects, which again makes it different from these other movies, because not many people would be foolish enough to make a submarine movie. We were filming in the real submarine where we shot for two weeks, that was a tiny crew down below, and up above were makeup and hair with offices and toilets above, but down below was a crew of six or 7. And when we were shooting in the corridors there was just no room at all. And that definitely changed the way the actors felt because they understood what it was really like to be in that situation. But also it affects dramatically what you can do with the camera, and how you can move the actors. A lot of the tools that you were used to using you just can’t use. That really frustrated me, but I realized as I was cutting the film together that it also has this kind of benefit which is that it feels real. You know that camera has to be there because it can’t six inches further because there’s a metal wall. And so that I think began for me began to contribute to this sense of claustrophobia and we sort of went onto the sound stage, and I had made the sets so we could float whole walls, and decided we shouldn’t do that. I did ti the first day so that we could move the camera around, and it just felt wrong. It felt so completely wrong it was obvious to everyone instantly, so we put everything back and treated it like a real submarine instantly. The environment totally dictates how the film feels.

Did you have to storyboard a lot, considering the circumstances?

I did for the underwater scenes. That was actually the first time I did not just storyboarding but a pre-visualization of all of that. We didn’t follow it 100%, but because it is so difficult filming underwater, and you can’t really communicate with the actors, it was easy to tell them the shots they wanted to get. That was very useful for that. And another thing that we played around for a bit was how often to go outside the submarine, and see these CGI shots of a submarine being in the water. And to begin with, we did things which were a bit more complicated, camera moves around, and again that felt wrong because inside the submarine we were so restricted. We felt that we reduced the complexity of the camera movements even when we did have complete freedom. Because there’s something artificial about going for naturalism inside the submarine, and then suddenly your camera is outside the submarine. But you desperately needed those shots in terms of the rhythm of the editing and the storytelling. In a normal movie you’ve got an exterior of a house, those interstitial moments which are imbued with meeting around them are just pauses in the story, we didn’t really have those things.

I remember talking to Danny Boyle who did “Sunshine,” and he said that the hardest thing about doing that movie was that when you do a sci-fi movie, or a space movie, you realize that you get given nothing for free. And I think that’s what I realized. Normally when you make a movie you get so much that you didn’t pay for or plan. But when you make a movie in space, or underwater, it’s like every single thing you have to create.