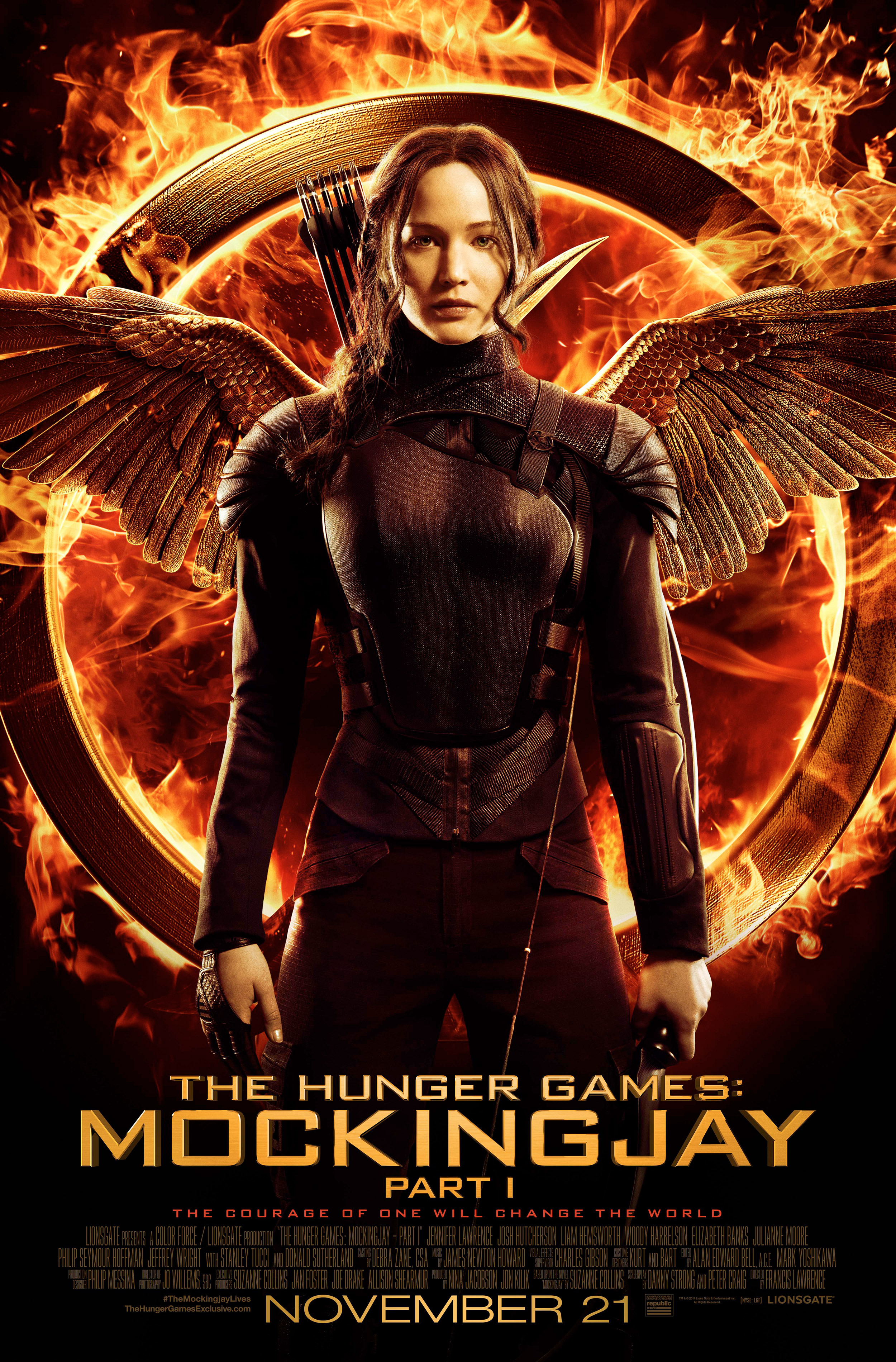

TSR Blog: How 'The Hunger Games: Mockingjay: Part 1' Loses to the Tyranny of Split Finales

The following contains spoilers for The Hunger Games: Mockingjay: Part 1. If the last five minutes of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire were like clinging to a pole for dear life with one arm and a whole lot of daddy issues this side of The Empire Strikes Back, its followup The Hunger Games: Mockingjay: Part 1 is like watching one trailer for Return of the Jedi over and over and over again, and then being told to wait another year to see what actually happens. With the revolution of Panem actually coming in 2015, the newest addition to the Hunger Games franchise has the ring of the distinctly less-thrilling episode of a TV series, where characters are treated more like chess pieces, being neatly put into place before a big strike … later.

The following contains spoilers for The Hunger Games: Mockingjay: Part 1. If the last five minutes of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire were like clinging to a pole for dear life with one arm and a whole lot of daddy issues this side of The Empire Strikes Back, its followup The Hunger Games: Mockingjay: Part 1 is like watching one trailer for Return of the Jedi over and over and over again, and then being told to wait another year to see what actually happens. With the revolution of Panem actually coming in 2015, the newest addition to the Hunger Games franchise has the ring of the distinctly less-thrilling episode of a TV series, where characters are treated more like chess pieces, being neatly put into place before a big strike … later.

The Hunger Games: Mockingjay: Part 1 is a part of a new phenomenon that is bigger than its own franchise, that of splitting finales in half. While previous blockbuster movements have bestowed the timeless hero arc with modifications like involving heroes with revolutions (as popularized with Star Wars, whose effect ripples to nearly every major sci-fi/fantasy messiah story now), the latest addition to the arcing franchise is to pointlessly stretch the material of one final book into two films. Although this method (made famous by Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 1) satisfies the futile-to-debate motivation of what scholar Mona-Lisa Saperstein would call “money, please!”, it’s a conceit whose inner corrosiveness is exposed in the latest Hunger Games film. Though harmless as it may seem to buddy up with these characters for a couple more hours, in its pointless narrative revolution of uncharacteristically dead pacing and cheap teases, The Hunger Games: Mockingjay: Part 1 exemplifies how the practice of finale splitting is a tyrannical disservice to a franchise’s structure itself.

The Rule of Three/If It Ain’t Broke, Don’t Split It

The first issue is basic, but nonetheless one that comes from our DNA. To quote philosopher Jaden Smith’s Twitter account, “Why Is It Always 3 WHY IS IT ALWAYS 3!!!!!” Indeed, it’s possibly a profound question, but one that can be answered in popular, ageless narrative structure - the almighty three act rule. Many arcing franchises (Star Wars, The Matrix, The Lord of the Rings, hell, even The Hobbit) have chosen to celebrate the number three because of the order it gives to their narrative strands when placing them within an arc that expands beyond one film. These steps are within our natural impulse in experiencing neat narratives, whatever the content: The hero journeys begin in part one, they dip down into definitive hardship in part two, and then they rise in part three. With this idea of three, themes and characters always have the ability for natural motion, whether they’re in the middle of climbing up or falling down. In the third act especially, they should be tighter than ever.

In what could have made this half-installment possibly unique, Mockingjay: Part 1 feigns no transformation to a structure that has worked for an infinite amount of narratives before it. The story boasts no new plot focus or distinct narrative features. Characters are simply delayed on their travels, with us paying for a full meal to watch them cook. Mockingjay: Part 1 is so useless because it doesn’t even to pretend to be more than purgatory, as if viewers are complicit to the Hunger Games creative forces slowing things down, our viewership of the previous two films consigning us to guarantee that we’ll stick around for the movie we actually want to see.

Treating Features as Teasers

Mockingjay: Part 1 shows the tyranny of split finales by aligning to another trend of the modern multiplex experience, that of the tempting tease. It’s no coincidence that this movie arrives in the fan environment of teasers for upcoming trailers, or in the time of post-credit stingers that become essential pieces to the development of feature films’ arcs. As movies progressively have to sell themselves as events, anticipating what’s coming soon becomes a hunger that can be hard to quell aside from pulling back the curtain. Even then, expectations from trailers made by third parties, along with marketing outside a film’s creative forces, can sell the same movie completely differently to people who want to know the most about something unseen — right until they see it.

The latest force to fall prey to this restless desire for spoilers of various degrees is the feature film experience itself, with how the super-expensive Mockingjay: Part 1 only presents teases of the stimulating elements that made for full viewings in the past two films. As a split finale, the structure of Mockingjay: Part 1 refrains from consistent portions of the good stuff. It can only pander to its expectations while trying to look like its actually a real movie: scenes of revolution become token, and the definitive charge from the two movies becomes only a promise, instead of a visceral force. As opposed to allowing a film to stand on its own, the need to split a finale in half leaves this tale to indeed directly echo Katniss’ latest, and most underwhelming objective - amuse followers with good enough propaganda for a future event.

Dawdling Defeats Immediacy

The effect of an elongated teaser as a stretched out half-third act creates a final problem that becomes specific to the standards of the Hunger Games series. The immediacy that previously defined a franchise based on do-or-die entertainment is tarnished with Mockingjay: Part 1, a tedious arrangement of figures. With all roads pointed towards the uprising that made the ending teases of Catching Fire so distinctly salivating, the setting of locked-and-loaded bunker District 13 proves claustrophobic in a way that is narratively unproductive. (The true hero of Mockingjay: Part 1 is Katniss’ weakness of green screen acting, otherwise 90% of the film would be confined inside District 13’s limited space.) Various tributes are reunited, and even the crowd-pleasing cat Buttercup is relocated. Along with the aforementioned insert revolution moments, what was once a vigorous franchise now asides to anticlimaxes, as with the gratuitous special-ops mission that ends relatively peacefully (except for Peeta’s psychological baggage). A thrill in Mockingjay: Part 1 also includes the ol' "forever shut door" race, a taunting gesture to the film's audience.

With only more exposition used for narrative oxygen, Mockingjay: Part 1 expresses that delaying the magnitude of a final act is most of all directly counterproductive to everything built before it. While the first two films built it all up and created a tense yearly tradition, Mockingjay: Part 1 transitions from this focus with little guff; it is the first film in the franchise that manages to stoke a revolution, but not its audience.

Conclusion: Part 1

The trend of the split finale might have actually started with good intentions. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1 and Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 inevitably conjured a galaxy-load of moolah for its creators, but the method had some arguable heart regarding its acknowledgement of the relationship audiences had built with its characters over six films. Spinning eight films out of seven wasn’t such an unreasonable extra step, especially with the original adapted final Harry Potter book spanning 759 pages (compared to the 390 total of Suzanne Collins’ “Mockingjay”). But still Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 1 introduced the problem that is now celebrated by Mockingjay: Part 1: whatever tone or tension might be achieved, it feels like half a movie, nonetheless the meandering expositional half.

Conclusion: Part 2

There is some dark irony to be found in Hollywood’s fixation on extending the finale, a type of cash-grabbing conceit that actively works against creative intent. For one, the strong franchise-ending film remains further elusive, the arcing narrative’s third act more associated with shark-jumping than tidy endings; even Christopher Nolan stated “There are very few, very great third films,” before further proving this with his 2012 film The Dark Knight Rises. Secondly, by messing with a third act tightness that goes beyond the material but to structure itself, franchises are in danger of debasing their big kahuna selling points, tripping up their big moments by biding time with exposition that the previous blueprints weren’t prepared for.

Nonetheless, the split finale puts another stake in the belief that stories can have monetary momentum if they’re simply good enough. Now with yearly YA followups (Mockingjay: Part 2 is due November 20, 2015, the Divergent-ending Allegiant will follow split course) the yearly tradition of franchise-supporting is ready for misuse by the structure-changing split finale. Studios now have a trendy excuse to return their product to the multiplex with one extra, indeed cheapened, half feature installment.