TOP 7 Biggest Changes in Baz Luhrmann's 'Great Gatsby' Adaptation

We start the Top 7. You finish the Top 10.

We start the Top 7. You finish the Top 10.

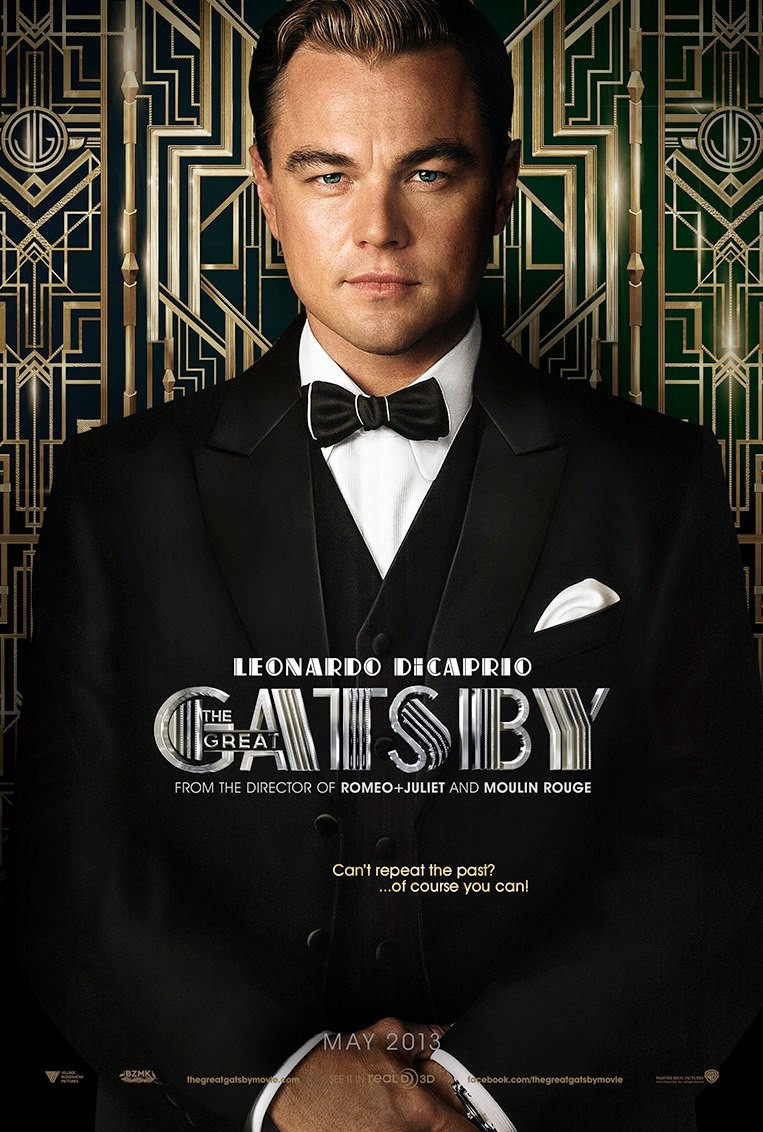

While modern Hollywood may always be ravenous for an adaptation, no director has such a unique taste for giving classic literature the poppy cinematic treatment like director Baz Luhrmann. In 1996, he helmed Romeo + Juliet, which used dialogue ripped right from Shakespeare's text, and placed the story into a contemporary setting enlivened by a thoroughly '90s soundtrack.

Luhrmann's latest attempt at sprucing up a classic comes with The Great Gatsby, an adaptation that respects the time period of F. Scott Fitzgerald's famous novel, but utilizes a contemporary soundtrack and a wild color palette. This version of Great Gatsby overall remains fairly faithful to its source material, honoring sections of dialogue verbatim, and slimming down the novel's gorgeous narration. However, there are some curious additions and omissions in this film, which I'm going to discuss here.

With full spoilers to the movie and the book, here are the TOP 7 Biggest Changes in Baz Luhrmann's Great Gatsby Adaptation ...

7. Buchanan and Gatsby's coupé rage

The movie: The violent masculine tension between Tom Buchanan and Gatsby in the third act is given a physical example with a reckless driving scene, in which the two are speeding to get to New York. They move in and out of both lanes of traffic, to the terror of the other passengers in their car. The book: The collective groups of Daisy & Gatsby and Tom & Jordan & Nick do ride into the city on the hot summer day in two separate cars, but there is no race between them, nor a moment of motor pushing. Instead, this moment on the road (in which Tom and company leave before Gatsby and Daisy) becomes a time for Tom to express even more hostility towards Gatsby, laughing at the millionaire's Oxford background, among other things. As indicated in Chapter VII, the three have this brief discussion, but then they drive "for a while in silence" before pulling up to George Wilson's gas station.

6. Nudges at Nick's possible homosexual experience

The movie: There is no illusion to Nick having any type of homosexual episode during the party in New York after he first meets Myrtle, or in any moment in the film at all. Instead, it is more hinted that Nick has a heterosexual moment with one of Myrtle's New York compadres, her sister Catherine, all in the midst of getting "roaring drunk." The book: As indicated at the end of Chapter II, "pale feminine man" Mr. McKee has a longer interaction with Nick. After Tom hits Daisy and causes chaos to the drinking party, Nick follows Mr. McKee out the apartment door, and to the elevator. Moments later, after McKee invites Nick to lunch "anywhere," the following paragraph begins like this: ". . . I was standing beside his bed and he was sitting up between the sheets, clad in his underwear, with a great portfolio in his hands."

5. Relationship between Nick Carraway & Jordan Baker

The movie: The relationship between Nick and Jordan is that of two good friends, in which they could have interest in each other, but we are never shown them acting on it. They are like two single friends who might eventually hook up, despite all of the drama going on with Gatsby and the two Buchanans. The book: There is at least one instance in which the two have physical chemistry, such as at the end of Chapter IV, on a walk with Jordan through the city. After a night having spent time together, the narration states, "Unlike Gatsby and Tom Buchanan I had no girl whose disembodied face floated along the dark cornices and blinding signs so I drew up the girl beside me, tightening my arms. Her wan scornful mouth smiled and so I drew her up again, closer, this time to my face."

4. The back-story of "old sport"

The movie: In one of Luhrmann's goofier visual moments, he provides the backstory for why Gatsby says "old sport" like he has very polite Tourette's. Complete with a mustached man screaming "OOOLLLDDD SPOOORRRTTT!" in dramatic slow motion, the script tells us that Gatsby picked it up directly from his unofficial guardian Dan Cody, with the term gaining significance even in a life-or-death situation. Reason: No such story is provided in Fitzgerald's novel. There is an instance in Chapter VI when tension between Tom and Gatsby is heating up, in which Tom inquires about the expression. However, Daisy shuts that interrogation down instantly, and instead tells him to order up for ice.

3. Gatsby's funeral

The movie: The death of Gatsby is turned into another circus, this one at the expense of his postmortem reverence. Photographers are shown crowding around the man's casket, their flash bulbs lighting up his corpse. In his voice-over, Carraway indicates that no one showed up for Gatsby's funeral. The book: The book takes the phrase "nobody came" as a technicality, when actually a few people do attend Gatsby's funeral. In a sweet scene that brings the mystery of Jay Gatsby full circle, Gatsby's father Henry C. Gatz arrives at the mansion to attend the funeral, and to witness firsthand the extravagance cultivated by his son. According to Chapter IX, the funeral is also attended by "four or five servants and the postman from West Egg." A man that Nick and Jordan met in the library earlier also shows up, concluding a paragraph by calling Gatsby a "poor son-of-a-bitch."

2. The significance of the title "The Great Gatsby"

The movie: A fittingly cheesy conclusion to a terrible framing device (more on that below), Carraway is seen titling the writing project he had been working on throughout the narrative. Originally titled "Gatsby," we watch him hesitate and then scribble "The Great" on top of that word. The book: While the book certainly plays out like a manuscript written by Carraway, the most romantic writer to ever work as a bondsman, there is absolutely no scene such as this in which the book references its own creation. Even history tells us that Fitzgerald wasn't satisfied with the final book title. He had instead considered very different titles, including "Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires," "Trimalchio in West Egg," "Trimalchio," "On the Road to West Egg," "Gold-hatted Gatsby," and "The High-bouncing Lover."

1. Framing and placement of narrative

The movie: Maybe because he's burned out by 1920s nuttiness, our narrator Carraway randomly now mulls about in a sanitarium. While there, he is encouraged by his doctors to write about his experience, which turns into the story we now know as "The Great Gatsby." As mentioned above, there is even a moment at the end in which Carraway looks over his manuscript, titled "Gatsby," and then adds "The Great" on top of the last name. The book: Regardless as to whether such a framing device was considered horrifically cheesy in the 1920s, Fitzgerald avoids anything like this, and instead places his narrator's voice in a time that is simply post-Gatsby. That's all that needs to be said. While Luhrmann's film has numerous missteps, nothing is worse than his choice to shamelessly frame this story with something so obvious. It is but one of many examples in which Luhrmann's version of Great Gatsby doesn't service the source material by making everything bigger.