"I think that we could all do with a healthy dose of disillusionment," remarks director Bennett Miller while recently speaking in Chicago about his new film Foxcatcher. It's a statement delivered with his zen garden-like tone (Mark Ruffalo's words, not mine), and with truth concerning his dramatic pursuits as a storyteller. Foxcatcher, like his previous projects Capote and Moneyball, explores characters and systems that audiences may recognize, but with dramatic ambition then seeks to unravel it in a colder light.

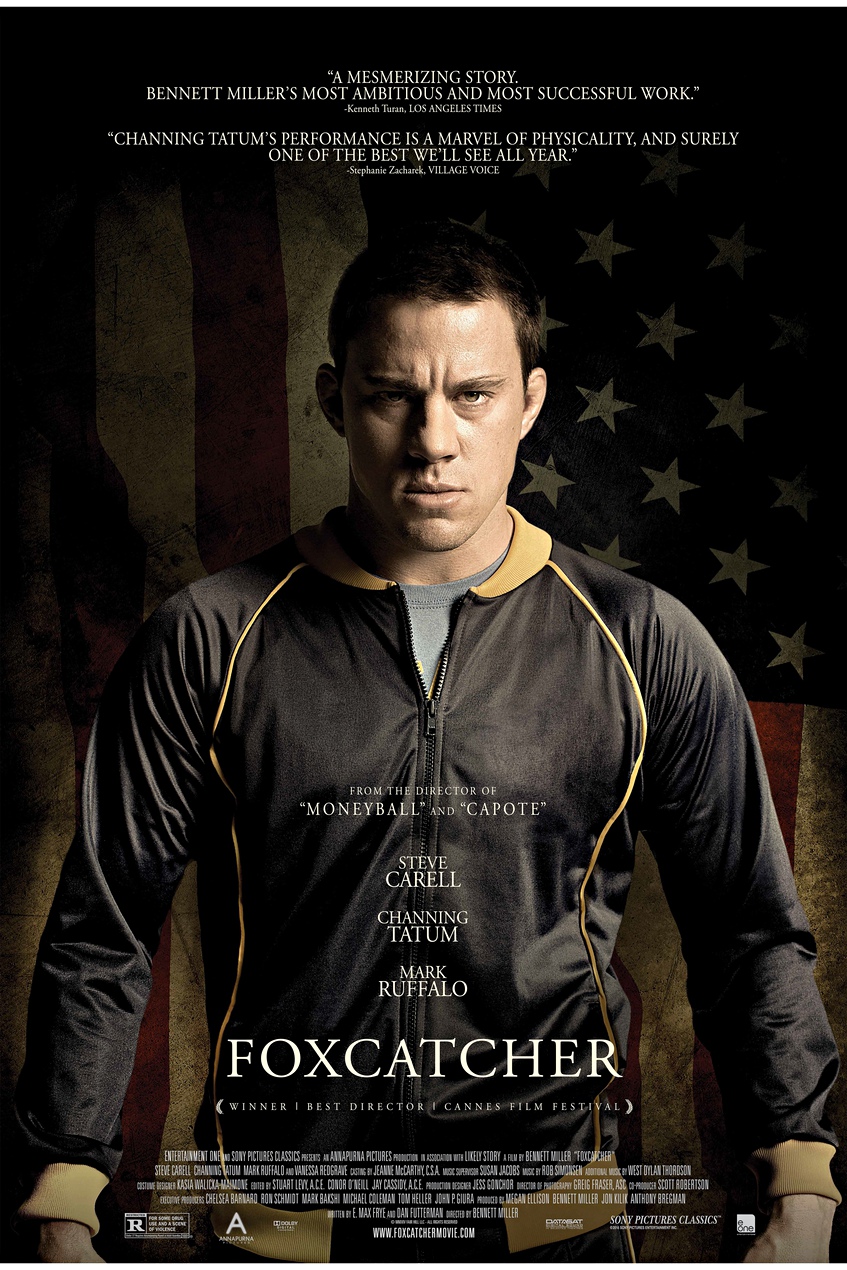

A riveting true story about Olympic wrestling brothers Mark and David Schultz (Channing Tatum and Ruffalo, respectively) and the billionaire who wanted to own their glory (Steve Carell), Foxcatcher is an observational drama on the morose results of the American Dream, and the ideals that create selfish ambition. Miller is certainly aiming high with his material, and mostly achieves this desired prominence with the help of larger-than-life performances.

"I think that we could all do with a healthy dose of disillusionment," remarks director Bennett Miller while recently speaking in Chicago about his new film Foxcatcher. It's a statement delivered with his zen garden-like tone (Mark Ruffalo's words, not mine), and with truth concerning his dramatic pursuits as a storyteller. Foxcatcher, like his previous projects Capote and Moneyball, explores characters and systems that audiences may recognize, but with dramatic ambition then seeks to unravel it in a colder light.

A riveting true story about Olympic wrestling brothers Mark and David Schultz (Channing Tatum and Ruffalo, respectively) and the billionaire who wanted to own their glory (Steve Carell), Foxcatcher is an observational drama on the morose results of the American Dream, and the ideals that create selfish ambition. Miller is certainly aiming high with his material, and mostly achieves this desired prominence with the help of larger-than-life performances.

This is Miller’s fourth film, having broken into the scene with his documentary The Cruise. Years later he went on to make Capote with his friend Philip Seymour Hoffman, and gave the late actor an Oscar for his performance as the title author. In 2011, Miller showed the number mechanics in a game of America’s pastime with Moneyball, starring Brad Pitt and Jonah Hill.

I sat down with Miller in a small roundtable interview to discuss Foxcatcher, how he didn’t have to beg to delay the film’s release for a year, the ecstatic realism on Carell’s face, and more.

Foxcatcher opens in Chicago on November 21.

What draws you to a subject?

Looking back I’d say I am attracted to outsider characters, I am attracted to people who are in worlds where they do not belong. I am interested in people from different worlds trying to operate together. Every one of my films has a person where he does not really belong with some great ambition ... which only occurred to me recently when someone pointed it out.

What was it about the world of wrestling that caught your eye?

Just that it’s a weirdo sport, it’s a subculture. People who wrestle belong to a sect. I knew nothing about wrestling, and [for Foxcatcher] I was of course drawn in by the story, the oddity of one of the wealthiest men in America having this sect move onto his property with some declarative goal so huge, patriotic ambition, and it ending tragically, was just too much to resist. Of course, once I started researching and getting to know about wrestling, I realized that it’s an amazing sport, and I began to understand why it’s not a popular sport, and I think it has something to do with the fact that it’s hard to understand and appreciate. It’s not like boxing where it’s pretty clear what’s going on, not that boxing doesn’t have its nuances. It’s really more like chess, and you have to be trained to grasp what’s going on to appreciate the sport, but also to learn about the fraternity and the community of wrestlers and the common virtues that they share, the absence of material reward. You’re not going to get rich or famous off wrestling, period. Therefore, the reasons to pursue this, possibly the most difficult reasons in the world have to be for intrinsic values of it, and that’s fascinating. Who does that? Not for the extrinsic award, which is more the interest of the Du Pont, who is just going to take this sport of fraternity and sport and exploit it for his own personal gain.

How did you want to go about tackling the mystery of 'Foxcatcher’s' events?

I do think about learning without including. The film doesn’t tell a story so much as observe a story, and I think there is a temptation to make inclusions along the way, to put a point on things, and this is not that. The film restrains itself from simplifying with conclusions good or evil, labels, the moment you make a conclusion about something. Everything that we might know about these themes that are woven throughout this story from class and wealth and entitlement, I didn’t want to just regurgitate an attitude about any of these things, but look at where the rubber hits the road with these classes, and try to observe in an unflinching way something that isn’t easy to look at. Because we want to get there and have that opinion about it, but my feeling is that if you can discipline yourself to not react like that, and to look past things that there are discoveries to be made that are otherwise obscured by the polarizing impulses.

When doing all of the research through what has already been expressed about this story, how do you sift out the human connection?

It was from talking to everybody at length, over long stretches of time. Conversations that began eight years ago and continued through the edit, with Mark Schultz, with [David's wife] Nancy Schultz, the police who worked on the estate, with the son of the chauffeur who was paid to be Jon’s friends, dozens of people, and just cultivating relationships with all of these people. At any moment I could just call them up and in certain cases, meet. I went to wrestling tournaments where where all these guys meet.

The nose on John du Pont's face seems to take on a meaning of its own, as if representing the truth in Carell's character, but making his appearance seem bigger than a regular human being. How did you want to go about handling the distinct features of a character that make him so cinematic?

It is an incredible coincidence that it fits in there like that. Not a lot was imagined. It’s awfully accurate - that is a replica of the guy’s nose. It really looks similar to the real du Pont. I have to acknowledge the artistry of our makeup artist Bill Corso, who really worked on this character the same way that Steve Carell worked on his character, the same way any actor would work on a character. Months and many makeup tests and camera tests to work on this character so that it would read that there is something regal and grotesque, and ironically ornithological. He’s literally got a beak. That scene in the gym where he has the profile, it just happens that the guy who said “My friends call me Eagle,” and he’s just got this beak. It’s too good. I wish that any of us were so clever to have conceived that cocktail, but it’s really just drawn out truth - that is his name, that’s what he wanted people to call him, he did have a beak.

What struck you about Channing Tatum that made you want him leading this project?

I offered him the part to him eight years ago after seeing A Guide to Recognizing Your Saints. I offered him the part before there was a script. I saw that film, and I was like, “Holy shit. This guy is electric, and dangerous, and dangerous in the way that he doesn’t even realize himself, and he’s a fully realized character, who can’t possibly understand how the world is seeing him.” And it was a role that he was playing that was really not similar to Channing at all. This is eight years ago, out of the gate. He really had an extraordinary performance in that film, and the physicality. It took six years to get to day one of principal photography [of Foxcatcher], and in that time, other roles came along in his career that have taken a totally different path. But to be honest I didn’t really watch much of those films, I was convinced early that whatever that was in A Guide to Recognizing Your Saints, I’m sure it’s still there. And when it was time to get the film going again and I revisited it with him, his level of commitment, seriousness, and intelligence about it was all very convincing. All of those other roles were just way-off in my periphery, I didn’t even look at it.

Mark is the center of the film, and yet he is more withdraw and silent than the two characters who drive the story, Dave and John. Was that a challenge?

It seemed sort of in a way obvious. It would have been possible to have made this film without Mark Schultz at all, it would have been Dave Schulz and John du Pont and many involved with the story itself were surprised that Mark was even featured in the movie at all, much less the center of it. But as I researched the story, it seemed clear that this relationship between du Pont and Mark, followed by du Pont and Dave, followed by what happened, was the story. And understanding these characters through that relationship with Mark and the du Pont relationship seemed to make sense. And the fact that he was animalistic and not communicative is also part of the film, it’s also another theme in the movie of male non-communication.

One of ‘Foxcatcher’s’ key creative forces is Megan Ellison, renowned producer for recent films like ‘Her,’ ‘American Hustle,’ and ‘The Master’. What kind of influence did she have on ‘Foxcatcher’ that might have been different from any of your previous collaborations?

When you work with Megan, there’s no possibility of being at odds with competing interests. If you’re working in film, you have to be financed, which means that there is a collaboration with an entity that has separate interests. Your interests cannot be identical. Everybody could want a great movie, but that’s not the whole of it. Nobody wants to lose money, but with Megan - she doesn’t want to lose money either - but once she commits to something, the governing principle comes from her desire for it to be everything that it’s meant to be; that’s it. We were meant to release this movie last year, and we needed a few more months, I think we were all prepared to bear down and get it done, and it was her that made the decision that the film would benefit, despite some additional expenses, that it would benefit from more time to gestate. That is the mark of a producer. She actually led that. It’s not like I’m begging. It also can be crazy making [a film] if the competing interests of those who have a financial stake in the film are broadcasting their anxiety over creative decisions, But I think the process is truly exceptional with Megan. Your interests are the same.

How did ‘Foxcatcher’ evolve during that extra time of post-production?

We had to reshoot one little thing which was not even half a day. The way I make all of my films so far has been very similar in that it’s a process of experiment and discovery from beginning until end, you’ve got three major periods to get it right. In the development of writing, the conception, the shooting, and post-production. The film is constantly, every beat is being challenged in the engineering of the film is being questioned throughout all three stages, but the initial conception of the film, the character and the spirit of it, I think remained consistent. How it materialized, and how it was to incarnate, is what is explored and discovered. But it really did begin with a feeling, that feeling that you have for a film when you walk out of it. That’s what you get possessed with, and you’re looking for a way for that to materialize. It’s really constantly questioning, blowing it up, putting it back together.

You're approaching your films from a cinematic view, while also coming from a storytelling perspective that trying to not hand the audiences what they expect. Is that something you are very conscious of when making your films, or something you are specifically working towards?

Yeah, without a doubt. The austere style, that observes and does not tell. I think the other thing is boring, I really do. I don’t need to see one more romanticized version of any story ever for the rest of my life, I really don’t. I don’t need those tingly feelings. I think that we can all do with a healthy dose of disillusionment; disillusionment isn’t a bad thing, it means enlightenment. Entertainment is entertainment and there is absolutely a value and a place and I don’t condemn any of it, but for me, personally, what I find satisfying is to be challenged and to see something that is provocative and truthful and is not putting me on and pushing my buttons, or selling me some romanticized shtick that makes me feel sweet and tingly about something.

This is not the reason or the motivation [for Foxcatcher], but it was an added interest for me that it was a story that was covered by the media. The news trucks racing down to Du Pont's mansion, and there were also a couple of books written about it. And the version that does enter into the airwaves has a particular nature to it. It is a sensational thing that we can consume like potato chips. But when I started researching and talking to people who had things to do with the story, I discovered the aspects of the story that were completely neglected in any coverage of it, 'A," and "B," the things that really only cinema can convey. Cinema can shine a light where no other medium can, and so it’s not just the story or the facts, but it’s a three-dimensional complex of art forms that can realize a story. I’m thinking of something that people involved in the story had said ... I started getting people’s responses from the movie, and he said that he was there the day of [an important climactic moment]. Though he knew the story inside and out, it made it more real than what happened, because it’s experiential.