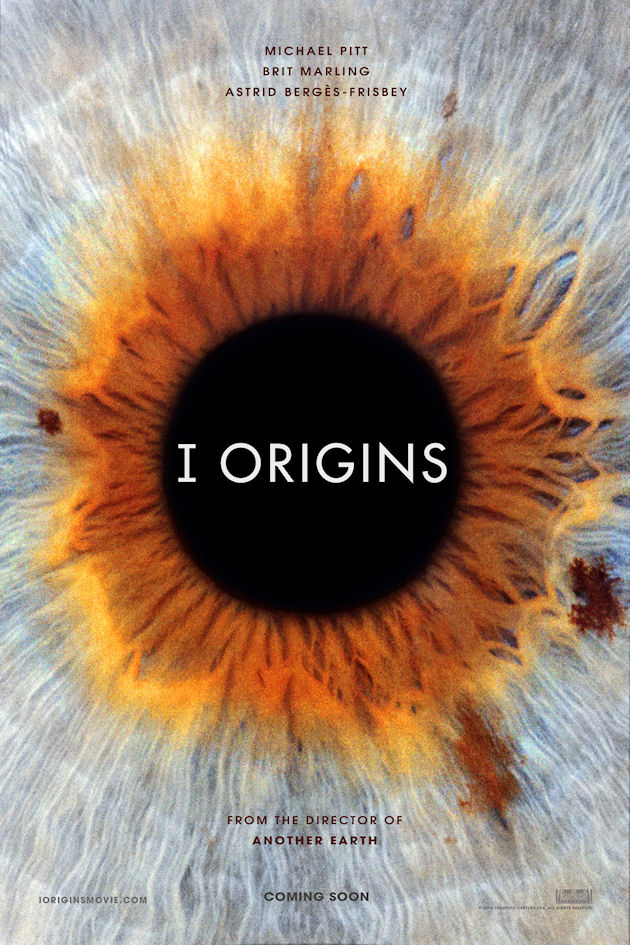

Mike Cahill's I Origins is sci-fi semi-thriller that takes the debate of science and religion to the unexplainable mystery of the human eye. Actor Michael Pitt plays Ian, a scientist who seeks to find a cure for blindness in order to disprove Creationism. More questions than answers are provided, however, when Ian finds himself in a spiritual journey that challenges his cause-and-effect convictions.

Pitt has worked with an impressive amount of directors in a career that is just starting, with names that include Martin Scorsese, Michael Haneke, and Bernardo Bertolucci. I Origins is the second film written and directed by Cahill, who works with a larger scale production this round compared to his tiny debut Another Earth.

Mike Cahill's I Origins is sci-fi semi-thriller that takes the debate of science and religion to the unexplainable mystery of the human eye. Actor Michael Pitt plays Ian, a scientist who seeks to find a cure for blindness in order to disprove Creationism. More questions than answers are provided, however, when Ian finds himself in a spiritual journey that challenges his cause-and-effect convictions.

Pitt has worked with an impressive amount of directors in a career that is just starting, with names that include Martin Scorsese, Michael Haneke, and Bernardo Bertolucci. I Origins is the second film written and directed by Cahill, who works with a larger scale production this round compared to his tiny debut Another Earth.

I sat down in a roundtable interview with Cahill and Pitt to discuss the film, what intrigues them about the other, the preparation they did for such a science-heavy movie, and more.

I Origins opens in Chicago on July 25th.

Michael, considering all of the directors you have previously worked with, what was new about the experience of working with Mike Cahill?

Michael Pitt: I can't say enough nice things abut working with Mike. I've been very blessed to work very closely with some really great directors. But I'm really trying to be active in working with filmmakers now who understand where film is going, and are paving the way, and are changing things. Mike is definitely a filmmaker like that. He's trying to do very difficult things, and he's just going to get better and better. Normally, to be honest, I don't see that very often with new filmmakers. I think the easiest way to explain it is that less experienced filmmakers, I find, get so tight to the script that they get lost, and forget that cinema is about catching the moment. Or, they're so loose and interested in that moment that they have no vision. Whether he's aware of it or not, which I am still wondering myself, Mike has got both. That's something that normally the directors.

One of the things that is fascinating about your films is the balance of belief and disbelief. You say faith vs. facts, science vs. religion. How do you go about creating characters and storylines that present both sides fairly, but still honestly?

Mike Cahill: This character, Ian, I have to give it to Michael for the creation of that three dimensional character. In constructing Ian, Ian is a complicated guy. He's a guy who believes in science, in scientific evidence, in fact and method to test things. Only at the end of that process will he believe in something, right? And yet, he follows a bunch of numerical elevens and gets on a bus, and that doesn't seem to jive as a person on paper, and yet that somehow resonates as a person in real life that is 95% one thing, and 5% something else. And so in constructing that character, we talked about this a lot in how it's something itching at him, and there's a resistance to it, but he knows it's there. But part of his attraction to Sofi (Astrid Berges-Frisbey) is the fact that she saw that tiny little bit like a string coming out of a suit, and started pulling on it, and pulling on it. The seams started unravelling. And so that is engaging to me, the idea of taking someone who is like this Dokkenesque, resistant, almost believes or completely believes that religion is dangerous, and putting them in a situation where love and faith is the only thing that they can hold onto.

Michael, you prepared the science part of the character when you were helping develop Ian. How do you balance boning up on the science and getting the science mindset with the emotions of Ian, and how he responds to love in the spiritual sense?

Pitt: Every project is different, but normally I am fan of researching, researching, researching, and then throwing it away. When you train as a boxer, you're practicing a punch super slow, and you're getting that muscle memory. When you get in the ring, you don't think about that. Acting is very similar, which is like repetition, repetition. You get those things inside you, and forget about them so that when the director puts you in this world, you react, and hopefully you've done your work. That's usually when it's the best, when it's second nature. It's very time consuming.

Cahill: To add to the process, we went to Johns Hopkins laboratories, and learned how to extract DNA, and whatnot. This guy Phil, a scientist there, he's been in the lab for thirty years, and one of the things that he does is pipetting salines. There's a rhythm to it, and a quickness. Michael said to him, "Don't show me how to do it, just do it. Can I observe you for a while?" And he just watched, and was sucking it up like a sponge, so that now in the movie, all of those scientists who watch it are so blown away by how that mannerism is just shedding off of him.

Mike, do you think it is possible for a fictional narrative to do more than ask questions? Does fictional film have any business trying to show the possibility of miracles?

Cahill: Since the dawn of civilization we have been trying to construct narratives that make us feel peaceful. The thing is that we don't ask questions and leave them wide open. It's very precise, in that the audience puts themselves there, and puts their belief on the table as well. That's part of the experience.