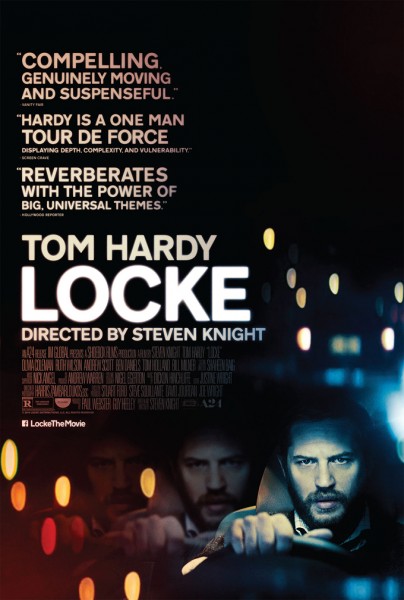

Having scripted films like Eastern Promises and Closed Circuit, Steven Knight will argue to you that he writes conventional Hollywood stories that get made into conventional films. However, as a burgeoning director, he distances from such expectation with his second behind-the-camera project Locke, which stars The Dark Knight Rises star Tom Hardy in a car, dealing with an "ordinary tragedy" all while driving in the middle of the night. A handsfree version of My Dinner with Andre filmmaking, Locke is a creative force that shows the potential of voice performance and dialogue for vivid storytelling, and features a landmark performance from Hardy.

Knight previously directed the curious Jason Statham drama Redemption, which is known by the less embarrassing title of Hummingbird elsewhere in the world. Amongst many projects listed on IMDb, Knight is currently scripting The Hundred-Foot Journey which is set to star Helen Mirren, along with a mysterious WWII film with Brad Pitt. His contributing work on Seventh Son will be shown when that long-delayed movie is finally released in the beginning of 2015.

Having scripted films like Eastern Promises and Closed Circuit, Steven Knight will argue to you that he writes conventional Hollywood stories that get made into conventional films. However, as a burgeoning director, he distances from such expectation with his second behind-the-camera project Locke, which stars The Dark Knight Rises star Tom Hardy in a car, dealing with an "ordinary tragedy" all while driving in the middle of the night. A handsfree version of My Dinner with Andre filmmaking, Locke is a creative force that shows the potential of voice performance and dialogue for vivid storytelling, and features a landmark performance from Hardy.

Knight previously directed the curious Jason Statham drama Redemption, which is known by the less embarrassing title of Hummingbird elsewhere in the world. Amongst many projects listed on IMDb, Knight is currently scripting The Hundred-Foot Journey which is set to star Helen Mirren, along with a mysterious WWII film with Brad Pitt. His contributing work on Seventh Son will be shown when that long-delayed movie is finally released in the beginning of 2015.

I sat down with Knight in an exclusive interview to discuss his film, the conventions that it challenges, the difference of Hollywood movies sharing imagination instead of encouraging it, the film's appeal with "ordinary blokes," and more

Locke opens in Chicago on May 2.

Was the idea always to shoot on the highway, or was there a desire to shoot this film on the streets?

There's a journey that I do relatively often from Birmingham to London, and often at night. And I often think, especially when it is wet, that it looks really beautiful. When I made the film before this one [Redemption], we shot a lot of stuff from cars at night, and I just found it absolutely hypnotic. I really wanted the stage for this theater thing to be the motorway at night, because I think it's got a real quality to it.

In this regard, how much of this really had to be shot chronologically?

The great thing is that to begin with, whenever you're usually making a film, there's always the conventional way of doing it. But because I had a level of control, I said that I wanted to do it in a very particular way, which is you shoot it beginning to end, [and] you don't worry about continuity. Because the background is sort of chaos, it's lights and moving vehicles. Even if you could cut between different versions, which have actually been shot in vastly different parts of the motorway, nobody will know because it's still the motorway. So basically, we had the luxury of three cameras in the car which were rolling at all times, and the other actors were in a room in a hotel on a real phone line to the "set". I would cue the calls in sequence one after the other and we'd start at the beginning to the end, had a break, and then we'd shoot it again. So we tried to shoot it twice at night.

You've previously described 'Locke' like a radio play ...

Yeah, and like a theater play. All this is capturing the performance. The thing that I was interested in was getting the performance recorded in as many different ways as possible. The only breaks were that the RED camera has a memory card of 30 minutes, so we had to pull over and change the memory card, but then at the same time we changed lens and angle so that we had as much variety as possible, so by the end of [shooting] we got 16 different movies. We had so many different views of each moment. I always picked on the strength of performance.

How did you direct these radio actors?

We spent five days around a table with Tom and the other actors going through the script and getting character and direction, and what we needed, so that when we went on the road there was minimal amounts of that. But halfway through, because obviously we were shooting at night, and the actors would arrive at 9pm and work till 4am, halfway through I wrote letters to all of them slightly changing their characters a bit. We had shot it quite a few times with them being who they were. But for example, I wrote to Ruth Wilson "Try as you're actually glad he is going, you want him to go. This is your chance to get rid of him," and giving each of them a different idea, so that there would be a variety in their performance.

Given the shooting circumstances of this film, was the dialogue always solid?

Dialogue was always solid. The dialogue is pretty much word-for-word, and Tom also had cue in front of him, and also in the rear view mirror. The script is always there, and he likes to work from the script, rather than improvise, which is great, and the other actors had the script in front of them. The improvisation was in the performance. The words would be the same, but each performance was different.

Was there more time spent editing 'Locke' than usual?

Not really. We discovered that we kept returning to the same nights and the same sequences, where the performance is just right. You narrow it down.

How did you achieve those shots where it looks like he is still, but his car is moving forward and the reflected background is going backward?

That happens sometimes because of reflections. Because we shot it the way we did we could use happy accidents. Like when that truck comes in that says "It's always been," and it goes away.

How did the metaphor of concrete come into play? I know you have some previous work experience with concrete.

Only briefly. I worked with concrete when I was much younger. But I just learned that the arrival of concrete is the big day.

When did that become in this story?

The thing is that I wanted to point the camera not at a conventional situation that warrants a film, like a hostage situation or a murder or a crime of any sort, not even fraud. [Locke is] a very ordinary man who makes an ordinary mistake in an ordinary tragedy. In looking for what this ordinary man would do, then concrete appealed because of its possibilities as a metaphor for John Locke, a philosopher with his rationality and self-interest. So it was going always going to be about something solid, and someone who deals in concrete is about as solid as it gets. That's when that thought came in. I've always been fascinated by the people who take a piece of white grain and they build. Not the architect, but the blokes who are the unsung heroes, and oversee the whole thing. I spent some time with the engineer who helped build The Shard, which is one of the tallest buildings in London, and he didn't disappoint. A very down-to-Earth partner who spent sleepless nights worried about concrete, and sleeps in the construction site because he needs to be there at 3am. They're incredible people, and that's what I wanted Ivan to be. When he tells you his job, so what? But in fact, it's a huge business.

High stakes seems to be something that came from the get-go of this project's inception.

I really didn't want it to be anything that would make the papers or the local news. It was never going to be something that anyone else would be concerned with. For the people involved, it's the end of the world. Most of us live through that. Our dramas don't affect all people, but nevertheless they are huge dramas. Ordinary people could watch this and identify with his dilemma, you know, he's not Jason Bourne. He's a man who builds buildings.

Your previous directorial project 'Hummingbird' came with a lot of baggage given its star, Jason Statham. But then I've heard you say that 'Locke' is an anti-film ...

It's all about looking at the way films are made, and then thinking, "Is there another way of doing this basic thing which is get people in a room, turn off the lights, and then look at the screen?" There's got to be other ways of doing it. This sort of came out of that thought and that question, because there are always so many rules. Everyone seems to accept that in making a film. The obvious, logical way of ding some things never seems like the way it is to be done. I just wanted to do something that was almost naive in its simplicity.

Do you personally see this film as less accessible than 'Hummingbird'?

It was really important I thought, because the structure of it and the nature of it is quite experimental, to not have a situation where the film ends and people are thinking about the experimental nature of the structure. I really wanted people to have engaged with the character, and to have engaged with the story. And for that, pretty much around the world, people have responded in that way. They ask questions and say like, "This is the journey my dad never made," or "The journey that I never made." So many people hve identified with their dad, [it's] amazing. And they get very emotional about it, and it is so hard, but the experimental nature, its' not an art-house film. If anything, the blue collar response has been fantastic to this. Just ordinary blokes.

When a two-person film like 'Gravity' took off with mainstream audiences, was that a sigh of relief for you?

I don't see them as ... Gravity had the luxury of two people. They had the universe!

People always seem to be surprised when simplified small-quarter films take off. Do you think there's something to be said that it never has to be that complicated?

It may be a reaction to budgets and that special effects are so big now. The imagination is presented to you, and you just absorb it. It's someone else's imagination. With something like this, you are obliged to bring your imagination with you. One of the best things that people say is, "I forgot I didn't see the other characters." A couple people even said they thought they had seen the other characters. Like they had seen the wife at home.

Do you see yourself interested in more projects like this?

Yes. Absolutely. My day job is writing conventional Hollywood stories which get made into conventional films and its great and I love it. But if I'm doing it myself, I will do things differently.

Was 'Locke', then, a type of spark or creative reinvention for you?

I don't know. I think that these things happen organically in the world as responses to bigger trends. For me, it certainly feels like its going back to the most important place of the screen, which is the eyes of the actor. That's where people are looking. And you've got a good enough actor, that's enough.

Will you work with Hardy again in the future?

Yeah. He's brilliant. He's the best we got. And I'm hoping to shoot a new film early next year with him and another cast. I'm just working on it.

What was the first Tom Hardy movie you saw that really presented him to you?

Inception. I hadn't seen Bronson at the time.

Does everyone assume you would say 'Bronson'?

Yeah, I honestly don't watch a lot of films, deliberately. Mostly because of time and because I don't want to be someone whose work refers all the time to other people's films. I think its better to refer to things that really happen in the world.

How often do you go to theater?

Not very often. But at the moment, only when the film is ending. In our industry, a lot of that goes on. You can understand it, because people who are risking a lot of money, but they want to know what it is worth. There is a lot of precedent.

Were you able to sell this with any reference to any other movies?

This was sold on one paragraph. IM Global, bless them. They just said, "Yeah, alright." Tom Hardy was on board, and that certainly helps.