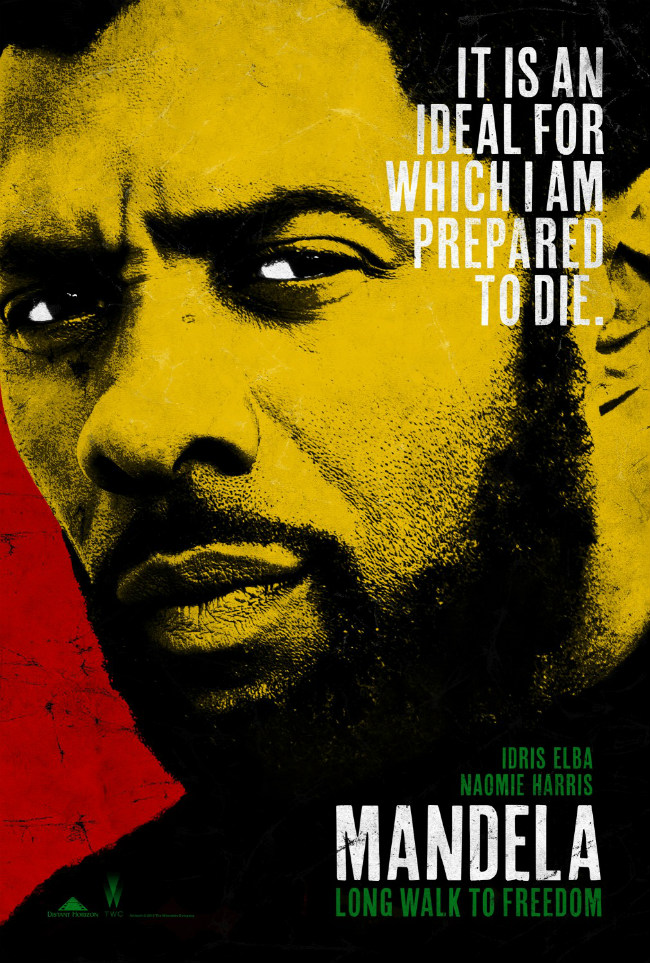

Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom is the long-gestating feature project about the famous South African leader Nelson Mandela and his wife, Winnie, each who played significant roles in their country's revolution against apartheid. Boasting the biggest budget for a film to come from South Africa, the film (as directed by Justin Chadwick), features spirited embodiments from Idris Elba and Naomie Harris (playing Nelson and Winnie, respectively) in its life-encompassing presentation of their heroic efforts.

Chadwick previously directed the Eric Bana, Scarlett Johansson and Natalie Portman drama The Other Bolelyn Girl, along with the 2010 drama The first Grader (set in Kenya).

Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom is the long-gestating feature project about the famous South African leader Nelson Mandela and his wife, Winnie, each who played significant roles in their country's revolution against apartheid. Boasting the biggest budget for a film to come from South Africa, the film (as directed by Justin Chadwick), features spirited embodiments from Idris Elba and Naomie Harris (playing Nelson and Winnie, respectively) in its life-encompassing presentation of their heroic efforts.

Chadwick previously directed the Eric Bana, Scarlett Johansson and Natalie Portman drama The Other Bolelyn Girl, along with the 2010 drama The first Grader (set in Kenya).

I sat down with Chadwick in an exclusive interview to discuss the film, its strength in extras, his disinterest in making the film "spinach," and more.

Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom opened in Chicago on December 25.

You've said previously about this project that you weren't interested in making a historical film. Do you think period films have been holing themselves into being, as you've defined them in the press notes, too "looky-likey"?

Well, it's just that you go to the cinema to be immersed in a world. When you see those period movies, there is a veneer between you and the characters, because the producers are spending thousands of dollars for you to see it in the wide. Why are we in the wide? Why do we have to see the horse and carriage ride? Biopics are incredible, and we talked about that in the early days of Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom. We have an expression in England, that we did not want this film to be like spinach - you know its good for you, but you go to the cinema which is expensive, and you want it to be visceral, and you want it to be emotional. There has to be a place in modern cinema for other stories of the world, and this chance to make an unbelievable story with the biggest budget that has come from South Africa. We had a responsibility to not make it spinach. To feel that you are actually in it, so that the film for me was about. It's also in terms of who I was talking to. Those who have been trying to make this film for years, they ask, "Have you seen The Elite Squad? Have you seen City of God?" I was using those films as references for what we were trying to do; to not have the wide shot, but to approach it as you would a modern movie. The prep that went into it was about making sure that this was an epic huge big visceral experience to the audience, and have great action and car chases, and would stand up against those Hollywood giants. But essentially everything had to be true, and real. It's a well-documented history, so there was no excuse not to get it right. And yes the period is right and its true, but with these 360 degree sets, Idris is actually there, and the music is playing, and actually being played by a musician or an activist that's actually from that period, who has worked with people on how to do it. That all informs the performances. That beginning was a better battle, because we knew it would be about performances. When Idris walked on the set, you could feel the energy of the crowd and the people, and that felt getting beyond a historical film, or a period movie. It was about trying to make it visceral and real and emotional, and that approach - everybody worked to achieve that. All the departments knew that was the way forward.

Considering the large scope of this film, was the control of thousands of extras the most difficult part in directing this project?

That was a huge challenge. I am from Manchester, England, so I haven't personally grown up in that struggle. I knew about it as a student, obviously. But going into South Africa I was very conscious, and I studied for a year, and listened and observed, and tried to understand all sides. When I started talking about it, there was an expectation from South Africa on how we were going to make this movie about their almost-god saintly character, which was quite right, because Mandela paved the way for forgiveness and freedom. But right away, I wanted the film to be a real visceral experience for the audience, and wanted to show the characters as flawed characters. The challenge was really to get everybody on a side, to shoot it in a way like those South American movies where you're in amongst it. Or like The Battle of Algiers. And this is recent history as well, so those townships still exist, and those people were living in the struggle and live in the struggle. From the beginning I said that we would incorporate those experiences and those people into the DNA of the film. We drop the audience in it, and we drop the actors in it. That caused people a bit of a panic at first, and people were thinking we should be using a studio in Cape Town, or a green screen. But we've got to shoot it for real. That was a huge challenge right from the beginning, but once everyone got on board with it, it was a huge driving force. When Winnie Mandela goes into a church, that's a church where actual atrocities have happened, with men and women who have seen those atrocities. It puts everyone in a certain space. You feel the emotion, and if it wasn't true, they'd have you, because this is their story, and these are their leaders. No matter how open-hearted and supportive they were, they would not take a lie.

How often did the extras directly influence the tone of the film?

All the time. I kept it so that when we had scenes where you wanted to capture the raw first feeling of it, I would talk to the crowd and hand it over to them really. I would say, "This is your history. A man is going to walk up there as Madiba, and I want you to listen to him, and to react to him in the way that you see fit. But I don't want acting, and I don't want untruths, and I don't want over-acting. I want you to feel and listen to what they say." And that was contagious a bit. Some reactions you see are from the first take.

How often were you able to use extras who have specific personal experience with Mandela?

I always tried to put in people who knew Mandela. There are some old ladies who knew him as a young man, and I put them around Idris on the steps of the courtroom. I am sure his heart was beating, and a couple of people even said to Idris things like, "Hey, he wouldn't say it like this, he would say it like that." But I think that such was, Idris is from London, and we had to be real to the people we were portraying. And this wasn't a look-like version, he had to capture the spirit of the man that he was portraying. It felt very important to have the man and have the man influence them. But as an independent movie financed out of Africa with no studio, I felt great responsibility given where the money was coming from, that the money was on-screen. And this was a huge story.

I read in the press notes that in the middle of your preparation for this project, you were able to view unreleased footage of the Mandelas.

I was given great freedom by the [Nelson Mandela Foundation]. No one said that I had to show it a certain way, but they knew I was showing these figures as men and women, showing their flaws as well as their attributes. I think I went in with a western-growing-up-in-England perception about who Winnie Mandela was, but it was a very different one when you are sitting with someone who is still living in Soweto now. I spent quite a lot of time with her, not as a journalist, just being with her as someone around her family, and then I found this footage in the archive that was nine rolls of 16mm film, from when she came out of solitary confinement after her 17 month stretch. I had seen the footage you can get on the internet of her, but I hadn't seen this footage of her after she had been abused physically and mentally, and not knowing where her children were. I showed that to Bill Nicholson the writer, and it gave a real deeper understanding that no one is all good or all bad. People are flawed. This is a woman who is being portrayed in so many different ways, but she is a mother, and a grandmother. What she went through felt very important for us to portray, and through the prism of this relationship, through the huge big arc of this story.

Quick Questions with Justin Chadwick

What did you have for breakfast this morning? I've had two breakfasts this morning. I had porridge, and then I had porridge, spinach, and avocado. And chili. Always start with a good breakfast, oh my goodness.

Favorite fruit? You can't beat a good apple.

If you could be someone else for 24 hours, who would you be? I'd love to be President Obama. I'd like to know what it feels like. No one really knows what it must feel like to have that responsibility.

Age of first kiss? 11. Yeah, at a school disco, in the coat room. It was a bit of a shock actually.