TSR Exclusive: 'The Armstrong Lie' Interview with Writer/Director Alex Gibney

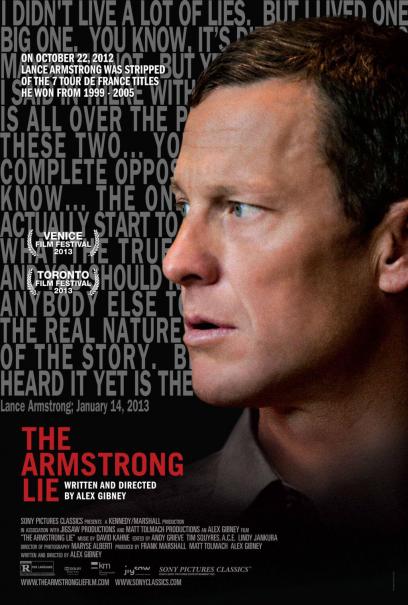

In 2009, cyclist Lance Armstrong wanted to prove his naysayers wrong. He came back from retirement, and touted that he'd win the Tour de France in order to prove to the world that his past seven wins were not boosted by any illegal enhancements. As with other chapters of his fascinating life, this comeback provided a great narrative, one made into a nearly-finished documentary project called "The Road Back," which had director Alex Gibney and his crew following Armstrong around as he hustled for another Tour de France victory. Matt Damon was signed on to do voiceover, and the project was co-produced by Spielberg's key producer Frank Marshall. "The Road Back" was then remodeled into The Armstrong Lie when the truth about Armstrong's doping began to make its way to the surface in 2012, both through teammate testimonies and a few select moments from Armstrong himself. Initially crafting what Armstrong associates thought would be a "puff piece," Gibney, with frustrations no more contained than any other disappointed witness to his twist, used his previously obtained footage to build up a piercing expose of Armstrong's falsities, while indicating that the full true story may only be ever known by Armstrong.

In 2009, cyclist Lance Armstrong wanted to prove his naysayers wrong. He came back from retirement, and touted that he'd win the Tour de France in order to prove to the world that his past seven wins were not boosted by any illegal enhancements. As with other chapters of his fascinating life, this comeback provided a great narrative, one made into a nearly-finished documentary project called "The Road Back," which had director Alex Gibney and his crew following Armstrong around as he hustled for another Tour de France victory. Matt Damon was signed on to do voiceover, and the project was co-produced by Spielberg's key producer Frank Marshall. "The Road Back" was then remodeled into The Armstrong Lie when the truth about Armstrong's doping began to make its way to the surface in 2012, both through teammate testimonies and a few select moments from Armstrong himself. Initially crafting what Armstrong associates thought would be a "puff piece," Gibney, with frustrations no more contained than any other disappointed witness to his twist, used his previously obtained footage to build up a piercing expose of Armstrong's falsities, while indicating that the full true story may only be ever known by Armstrong.

Gibney won an Oscar for helming 2007's Taxi to the Dark Side, and was nominated for a Grammy for his contribution to the Martin Scorsese produced TV series "The Blues." Often drawn to modern controversies, the highly prolific director has made films about Jack Abramoff (Casino Jack and the United States of Money), Julian Assange (We Steal Secrets: The Wikileaks Story), Eliot Spitzer (Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer), and infamous Cubs fan Steve Bartman (Catching Hell).

In an exclusive interview, I chatted with Gibney about his latest documentary, what learning Japanese taught him about filmmaking, the type of cheating that can be found in the film industry, and more.

The Armstrong Lie opens in Chicago on November 15.

Given that you are in the business of sharing other people's life narratives, do you feel Lance was one of the more aware subjects that you've dealt with?

[It was] unbelievable. It was as if he was the own actor/writer/director of his life. Everyday he would write the script, and then he would live it out. And he's good actor. He's a trifecta, a triple threat.

Did you ever wear a Livestrong bracelet?

No. I wore some Livestrong swag, but only after the Tour. We were handed out all this swag, I told my team that none of us were going to wear that. And still, we were branded as being in the tank for Lance anyway. We looked like a crew, but we were inside the barrier. There was a huge press crew around the Astana bus [the team that Armstrong was riding for], ten deep, trying to take pictures of Lance, and nobody was allowed inside but us. Everybody was looking at us.

In terms of going back to the original film with its new angle, did you write the voiceover first before going back into the edit?

No, not at all. I never do that. I almost always write the voice-over last. You hopefully want the sound and the images to rough things out. But it's never the other way around.

Within 'The Armstrong Lie' you use footage from Louis Malle's remarkable documentary short 'Vive le Tour,' which shows the experience of the Tour de France from decades ago, providing evidence that some aspects of the challenge have not changed. Specifically, when narrator Jean Bobet says, "The doped up athlete no longer knows his limits. He's nothing more than a pedaling machine," he might as well have been talking about Lance Armstrong. Did this documentary haunt your experience with the Tour de France, or making your own film?

I just flipped out. Somebody told me that Louis Malle did this documentary, and it was just fantastic. It was fantastic for all of the reasons that you should like the Tour de France, but also captured the out-of-control quality of it, which I thought was really interesting. I think that's also how Lance and Ferrarri kind of met. I think Lance allowed himself to be made into a pedaling machine by Ferrari.

As someone who participates in their own occupational marathons, and has won awards for such, do you find it frustrating particularly as a filmmaker to see cheating in sports? There's cheating in film, too. Particularly in award seasons; terrible cheating. It's the chatter that goes on around a film, the cheap innuendo, the way that people rig the voting rules. It doesn't mean the whole thing is crooked, it just means that ... it's not like the film business is pure, which isn't a surprise. But as far as I know there are no PEDs for film directors, sadly [laughs].

This reminds me of the Academy's horrible treatment in its documentary branch with Steve James and 'Hoop Dreams,' especially.

I didn't think The Interrupters got its due, either. I don't get it. Obviously Hoop Dreams was an extraordinary omission, but I'll never understand why The Interrupters didn't get more. Fantastic film.

You've made films about subjects from both the past and present. In your experience, can the truth be found better now, or with time?

I don't think there is any rule about that. I think you can be as fooled in the present also as you are going back in the past. It just depends on ... I think the trick as a filmmaker is that you want to be able to put yourself in a position of observing, and not prejudging too much, but then be able in the cutting room to make decisions about what you think really happened. And you don't necessarily have to wag a finger, or hold up a PowerPoint presentation. In fact, just the opposite. But I think that such is part of the editing process. Once you have gathered all of the evidence to assemble it into a story that recognizes the complexity and ambiguity of what you've seen, but also give some sense of what you think the truth has been. But I think, along the way, it is often useful to be fooled. It may be important to do so. You've got to be open, and if you're not open, you won't get fooled, but you won't learn as much. It's a little bit like, in an off-handed way, I remember when I was in college, I was trying to learn Japanese, which is a very hard language to learn. I had a pretty good accent, but I wasn't progressing as well as other people were in terms of being able to speak fluently, and my professor said, "You're not willing to make mistakes. You've got to speak often enough, and make horrible blundering mistakes, because it's the only way you'll learn." And it's a little bit like that in documentary. You've got to be able to observe, to believe, to become invested. To follow paths that you think might lead someplace, and not be too uptight about it. If you preselect or pre-edit, you don't take the journeys that you may need to understand what's ultimately going to happen.

This reminds me of Herzog's tendency to make up fake truths in his documentaries, like with the albino alligators in 'Cave of Forgotten Dreams.' What do you think then, of the concept of toying with truth to achieve a higher truth?

I think for me, I do believe in some of what Herzog says about that stuff, the accountant's truth versus the ecstatic truth. Sometimes I will fool the audience, intentionally, but will always come back around. Like in Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer, the first time you meet the person you think is the main escort that Spitzer is seeing, it's an interview with her, but it's not revealed for a little time longer that she's an actress. But you come back around to that. I think that is in the service of a different kind of the truth. You think about, "What if I presented this person as an actress upfront? Would people be focused on that instead of the other idea?" By presenting her as someone who you think that Spitzer slept with, you invest that moment and you're listening in a way that you wouldn't otherwise, which ended up being important. The whole story is about fooling people, you think you know something that don't actually know. The unknown known [laughs]. So the idea is that there are reasons to present things, and even in testimony, sometimes when you're in a live TV show and you have a political figure, it is important if you're the only one interviewing them to interrupt them, to contradict them. But I don't think that's what you should be doing when you're interviewing in this kind of a documentary. If someone is going to lie to you, sometimes that's important. And you may present it as if that should be believed, but then you'll come back around and realize that it shouldn't.

Does this experience make you skeptical about past subjects in your past documentaries?

I think about it all of the time. Nobody wants to be fooled, right? And that's why I think this film became so important, because I had been fooled to some extent, even though I was going against it. So sometimes I do think to other films and wonder if they got one over on me, or if I should have been more suspicious about their motives. There's a guy in Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, he's one of the people who is one of the strongest critics of the whole Enron thing. But he later went to prison for manipulating lawsuits.

As a firsthand spectator of the Tour de France, do you see the infamous mountain as a necessary evil?

That's why I think it's so appealing, and so romantic. It's the idea, this impossible task of exertion. What is it they say? To stay at weight in a mountain stage, you'd have to consume 27 cheeseburgers a day. The man against the mountain, the idea of embracing the pain, all that I think makes it a very romantic sport.

When you were watching it, and then making a film about it, did you get the feeling that human beings never were meant to do something as arduous as this?

I thought about that all the time. People were talking about how doping is dangerous, well, the fucking Tour de France is dangerous. They are literally sculpting their bodies because their bodies are devouring themselves, because they're so desperate for calories with the amount of energy that they're burning. I thought about that all of the time. And that's what we're interested in when watching sports, seeing people transcend their limits. And that's part of what pisses us off about doping. It's that doubt — you don't know. Yes, there's a competition going on, but you don't know at what point is the individual transcending their human limits, or are they just using a drug to do it. That was the mind-bender that Jonathan Vaughters faced when he set the record for climbing Mt. Ventoux, he got to the top and wondered, "It's supposed to feel good, but why doesn't it feel better?" He felt like he had just eaten the magic potion, and that took him up the mountain.

Do you feel you applied any more pressure to Lance in 2009 by making a documentary about his comeback?

I think it's self-imposed pressure. When he said, "I'm sorry for fucking up your documentary," I said, "Nobody fucks up my documentary," which turns out isn't true. But as I said afterward, I think there are parts of Lance that really meant what he said. He was used to fulfilling everyone's expectations, and the expectations were huge. I think the pressure on him was enormous, once he said he was going to do the comeback, he was going to win.

After promotion for this film is done, are you going to move on from this story? Or are you still keeping up with Lance's narrative? Have you seen the RAGBRAI video about Lance biking across Iowa in 2013?

I have not. But I do end up keeping up. I don't stop. And it's an occupational hazard, but one that I've found is pretty useful. The story gets under your skin, and you can't let it go.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oiBz3CvIVPo