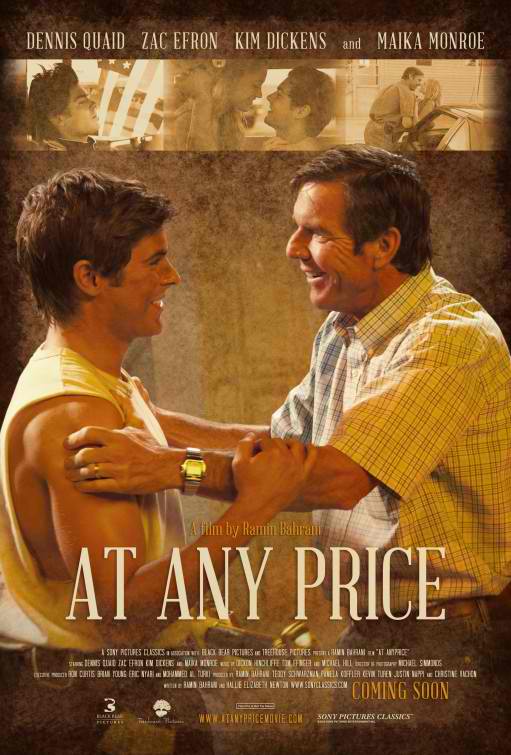

At Any Price is the story of Henry Whipple (Quaid), a family man running a large farming empire in Iowa corn country. He faces direct competition against Jim Johnson (Clancy Brown), along with opposition to continuing the family legacy from one of his sons, (played by Zac Efron). At Any Price is the story of an American salesman trying to survive brutal competition, especially when "Expand or Die" has become the mantra of all farmers.

Director Bahrani had been a top favorite director of late critic Roger Ebert, and previously has made films like Chop Shop, Goodbye Solo, and Man Push Cart. He co-wrote At Any Price with Hallie Elizabeth Newton.

At Any Price is the story of Henry Whipple (Quaid), a family man running a large farming empire in Iowa corn country. He faces direct competition against Jim Johnson (Clancy Brown), along with opposition to continuing the family legacy from one of his sons, (played by Zac Efron). At Any Price is the story of an American salesman trying to survive brutal competition, especially when "Expand or Die" has become the mantra of all farmers.

Director Bahrani had been a top favorite director of late critic Roger Ebert, and previously has made films like Chop Shop, Goodbye Solo, and Man Push Cart. He co-wrote At Any Price with Hallie Elizabeth Newton.

I sat down with Quaid and Rahmani in a roundtable interview to discuss At Any Price, its relevancy to the nation's economic crisis, Quaid's goals as an actor, and more.

At Any Price opens in Chicago on May 3.

Dennis, you said in the press notes that working with Ramin was special because he didn't let you use your "usual tricks." What did you mean by that?

Dennis Quaid: The reason I wanted to work with Ramin is in a way because of that. Chop Shop boy, the street merchant kid, what a performance. I said to him, "If you can get a performance out of me like that ..." It was non-acting, you felt like you were watching a documentary, as well as a film that had real social relevance to it. Like holding a mirror up to life.

That being said, what do you feel you've learned from your experience of working with Bahrani?

Ramin Bahrani: I certainly learned a lot working with him.

Quaid: I learned a lot about letting go ... just letting go of everything. What worked, and what didn't. How I look, and just putting my trust in Ramin. Every actor has their their thing you go to when you don't feel its not working or whatever, or what you had in mind.

Your explanation of "letting go" reminds me of your recent performances in 'Playing for Keeps' and 'What to Expect When You're Expecting' in which you play nuttier side characters who certainly seem unhinged.

Quaid: I've always been wanting to play as many different types of characters and roles in genres and films as I can. The only strategy I've had in my career is to try to do as many different types of things.

Bahrani: [Playing for Keeps] was on the airplane last night. We were flying here, and I said, "It's Dennis, it's you on the television!"

What connections do you feel this story of corn farmers has with the economic crisis that affects all Americans?

Bahrani: We're talking about economic crisis, which is also a social and moral crisis. The idea that one should keep expanding endlessly, while celebrating growth and stability, which I think doesn't make sense together. Just think about it. I lived with farmers for months. I was in Michigan, North Carolina, etc. All of them said "Expand or Die." I didn't make it up. Either they said, "Get big or get out," or "Expand or Die." "Expand or Die" means somebody has to die. Capitalism is an economic system that works, it works better than any other system we've managed to come up with in humanity so far. I think it does work. Right now the pragmatism is, "What's good for me should be endlessly bad for you, but endlessly good for me." This now we're getting into CEOs and major banks, running regulatory offices in D.C., etc. This doesn't make any sense. When those people have that much power and money, they create systems where they can continue to have more and more power and money, and that means that people like Henry Whipple have to resort to corruption to hold onto things. And it creates a feeling in him that he also has to keep expanding, otherwise he will die. Now this could be connected to anyone, to mom and pops who are competing against Wal-Mart. This pressure is felt across the board. I felt it when I lived with the farmers, [and] they were so welcoming of me. They said, "Come live in our home. Come make the movie here." They loved their neighbor, at the same time they were prepared to cut them out if it meant to survive. I don't think it's because they are bad people, I actually don't think Henry Whipple is a bad guy. He is quite nasty in the film, unlikable, in fact. But by the time the movie ends, I think, I hope, we can say that I empathize with this character, and I wish it had not been so.

Everybody was human in this film, even the bad guys. You have empathy for Whipple's competitor, Johnson.

Bahrani: There's something I love so much in that scene with Dennis and Clancy Brown in the diner at the end, like two giants of acting happening. That's what you want as a director. You want to do a couple over-the-shoulders, and get the hell out of the way. And what I find frightening about the scene is that Dennis wants to say something, but Clancy keeps saying, "Business is business." Dennis is like, "Please, tell me there's something more." As if they're both lost in a fog of money, and wanting to have more.

Do you think the problem in itself is capitalism? Do you think this has revealed a wall that exists?

Bahrani: My imagination doesn't go far in terms of economic or social systems to think of anything better. I think it's about the mass 99% finding some way to force things to change. How that's going to happen, I don't know. In fact, the conception of the idea of the 99% did change the election. Mother Jones revealing that 47%, I think that did change the election. I think a bunch of people didn't know what they wanted to say, so who cares if they had or didn't have a great policy, they had an emotional undercurrent that was correct. Kind of like a movie in which a movie is an emotional thing, and I could occupy anything, it was an emotion, it wasn't an economic policy. We are not going to sit there and be moved by an economic policy, but an emotion. And that's what a movie is supposed to do.

Quaid: I think as a society, things have been moving quicker and quicker. We're losing the humanity between each other. This film is Wall Street out in the cornfields, the only thing missing are the skyscrapers. It used to be about neighbor helping neighbor, and now it is about neighbor squeezing out the other neighbor. There's only so much land.

What struck you most about working with Efron? As he gets slightly older, he is taking on more roles that deal with mortality, and about coming of age.

Quaid: I think he's got all the tools in the box, this kid. He came out there as genuine and as a humble as he could be in approaching this role; very unpretentious and was out there to really try to do something. This wasn't just a career move for him.

Bahrani: For a guy who should have a big head he was the most down to earth, polite friendly guy you could imagine. He had read the script and I didn't even know. And my first thought was, I really liked him in Me and Orson Welles, which is the only film I had seen him in because it was Richard Linklater, who is a great filmmaker. I didn't know his other films. Paperboy (by Lee Daniels) was shot in the middle of my film. Zac and Dennis had other films to make, and I needed green corn. So I shot for two weeks every scene that involved green corn, and then I stopped for two months, they went and made other films, and they came back and finished the film.

Zac was doing re-shoots on New Year's Eve, so he was in New York. I went to meet with him, and he understood the part. He understood it so well that he said something to me and I added it in the script as a line of dialogue for the character. He knows. I told him once, and I don't think he understood what I said, but I decided to not tell him again because I thought it would make him conscious of the line. After we shot the scene I said, "Hey Zac, you realize you wrote that line of dialogue?" Dennis knows I did the same thing with him. I Googled Zac, and I hit video and I watched him on late night talk shows. And I didn't know what they were talking about, I turned down the volume. And then I noticed he would say some joke to Jimmy Fallon, and then look at the audience and laugh. I was like, "He looks diabolical. He looks mean. This could be great for the part!"

For Dennis, of course I've loved Dennis since I was a kid and have deep respect for Breaking Away, one of the great American films of our time. I clicked Dennis on Google, and then he's doing something on "Ellen," some improvisational comedy, "I'm Dennis Quaid, I'm Dennis Quaid." I was like, "I really like this." I called his agent and said "I love Dennis. Have you seen this Ellen appearance?" And the agent said, "Of course I have you idiot, I'm his agent!"

Quaid: And so I got the part, because of "Ellen."

There are two distinct scenes in the movie, in which various characters are seen reciting first the "National Anthem," and then "The Lord's Prayer." Was there any humor intended with these scenes, or irony?

Bahrani: Irony would be better than humor. And with the National Anthem, I noticed it shouldn't be cut off. I don't think I should it cut it out because that would be disrespectful. But I also saw there were storytelling in this scene, which I like. I would say more ironic, and I was thinking more about Altman, really. With my intention, I didn't know what I was gonna do. And when we were shooting the cemetery in the beginning, we brought in a zoom lens. And once you bring in a zoom lens you start thinking about Altman. And there's something so American about this film I hope you think about Altman, and there's something subversive about the film that I hope you think about Altman [again]. And that day I found my courage in the face of producers who said, "Why are you shooting the same thing over and over?" I said, "Robert Altman, I think, might do it."

With the Lord's Prayer, in editing you start thinking about Coppola, and you think of the ending Godfather. And you think, "How can you connect so many things in this scene with editing?" We worked a lot with the sound department to bring certain voices up during emotional moments.

Did working on this film effect the way you look at corn? Did it change your diet at all?

Bahrani: My diet had been effected prior by Jenni Jenkins, who was a dear friend of mine. Her and I did Plastic Bag together, and were involved in sustainability and media and creative ideas around sustainability. She turned me on Michael Pollan, and different ways of eating and buying food. Local, 100 mile diet. I started reading Michael Pollan's work, [which] led me to think about corn, and sent me out to the corn fields.

Quaid: It didn't really change my diet, I've always eaten everything.

Bahrani: "Dennis Quaid would like another steak!"

Quaid: "Are you gonna eat all that?" It really didn't change my diet. But everything is made from corn. Even the clothes we wear, and the products we put in our hair. Everything. If it wasn't for corn in society, we'd collapse. It's the true gold of our society.