'Beasts of the Southern Wild' interview with actors Dwight Henry and Quvenzhané Wallis

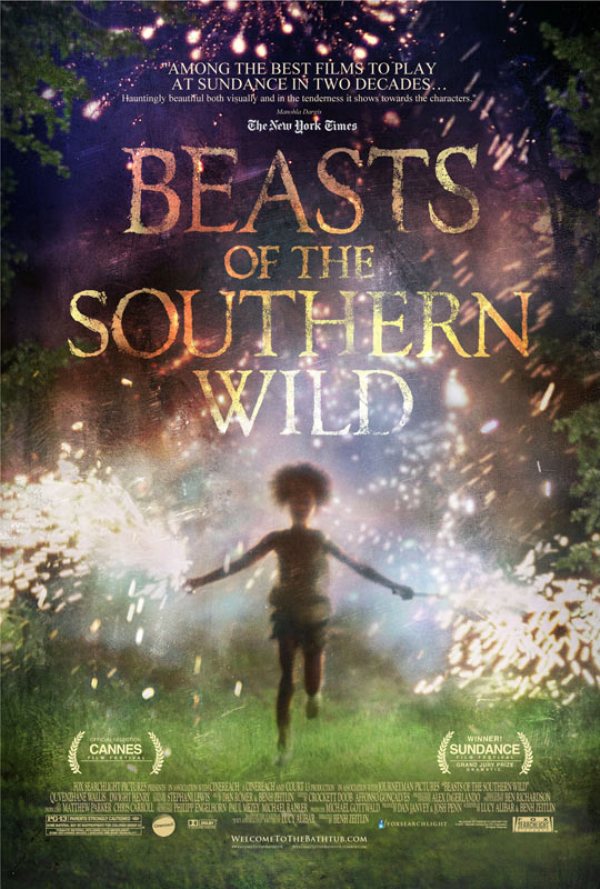

One of this film year's biggest discoveries has been Beasts of the Southern Wild, starring first-time actors Quvenzhané Wallis and Dwight Henry, as directed by first time helmer Benh Zeitlin. The aesthetic-driven indie film is about a father (Henry) and daughter (Wallis) who refuse to leave their hurricane-effected land near New Orleans called The Bathtub. After earning big receptions earlier this year from the Sundance and Cannes film festivals, eight-year-old Quvenzhané Wallis is now getting Whale Rider-like award buzz for her striking young performance. Dwight Henry, originally the owner of New Orleans' Buttermilk Drop Bakery and Cafe, has now taken on his second acting role in Steve McQueen's Twelve Years A Slave (opposite Michael Fassbender and Brad Pitt).

One of this film year's biggest discoveries has been Beasts of the Southern Wild, starring first-time actors Quvenzhané Wallis and Dwight Henry, as directed by first time helmer Benh Zeitlin. The aesthetic-driven indie film is about a father (Henry) and daughter (Wallis) who refuse to leave their hurricane-effected land near New Orleans called The Bathtub. After earning big receptions earlier this year from the Sundance and Cannes film festivals, eight-year-old Quvenzhané Wallis is now getting Whale Rider-like award buzz for her striking young performance. Dwight Henry, originally the owner of New Orleans' Buttermilk Drop Bakery and Cafe, has now taken on his second acting role in Steve McQueen's Twelve Years A Slave (opposite Michael Fassbender and Brad Pitt).

I sat down with the two first-time actors in a roundtable interview to discuss the spirit of New Orleans that is portrayed in the film, the experience of taking this movie to Sundance, and what eight-year-old Quvenzhané thought was the funnest part about making the film.

Beasts of the Southern Wild opens in Chicago July 6.

How do you feel this movie connects with people who have never even been to New Orleans?

Dwight Henry: It provides an awareness. Being from New Orleans, I want people to be aware of some of the difficulties that we go through, and see the strength that we have in ourselves through the worst type of situations. We seem to always recover; we have a strength that is unprecedented. Some of the situations we go through down there are problems we don't have to have, like flooding, which is caused by situations with the way they build things, when they revert water from one way to another way. Once the water comes in, the government has a way of building levees to make sure the water goes somewhere. Just like during the shoot, which was done in the Bayou, we had to deal with the BP oil spill. We had to relocate our whole set. There are all kinds of situations that we have to go through.

This movie was an opportunity for you as a person from New Orleans to express yourself.

Henry: Yes. I'm from that area, and these are actually things I've gone through in life. It's not just one incident that we're depicting in this movie. I was two years old living in the lower ninth ward when my parents had to put me on the roof of a house and wait for helicopters to come get me. In 2005, I had to evacuate my children, and displace my family. I bring a certain realness to this film; I was in Katrina in neck-high water. The possibility of the last catastrophe we had, they were talking about closing down the city, saying it wasn't a safe place to live. But guess what? No one left. It's a resilience that we have down there.

Despite the setting of this movie, and the many extras from the actual location, how unnatural was it to you to make this movie with the cameras and re-shoots, etc?

Henry: It wasn't as unnatural. To go through these things with cameras and lights, that didn't take away from the realness of what I went through. It was an easy transformation for me to go through doing this in real life and depicting it. It wasn't difficult for me. I had a lot of help from producers and Mr. Zeitlin. They worked with us on a lot of different things that we needed to know, and techniques that we needed to use. We had a lot of professional help to make a good film.

What was the funnest part of making the film?

Quvenzhané Wallis: Burping.

One of the most striking scenes was when Hushpuppy's place burns down. That must have been one of the craziest scenes to film, I imagine.

Wallis: You were the last one in the house.

Henry: It was a fun scene. It was a real controlled environment, and it was fun because it was something that we had never done before. It looked like it was unsafe, but it was fun. Quvenzhané was frightened. I understood certain things about the scene, but she brought the facial expressions. What you saw [on her face], it was real. I saw it in her eyes that there was a possibility [to her] that it could be real.

Wallis: I was very scared, because it was like BOOM!

Was dialogue improvised?

Henry: There was a lot of freedom. He would give us a script, and I'd read it. We'd talk about different things, and then he would take the script and throw it away - he would re-write the scene, and he wanted it in my words. If I was reading off a script, it wouldn't be as natural coming out. It seems more real and more natural like that. The same thing he did with Quvenzhané.

Wallis: He would let us highlight a line of dialogue, and we would have to study it. We would read it, take a break, and go back to it.

Henry: If she didn't like a word in the script, she would scratch it out and he would put that right in there for her.

Were you using a lot of our own words in your voiceover work?

Wallis: Yes. Sometimes I would read from the script because it was an easy line to say.

How much do you agree with the people in the film staying in The Bathtub?

Henry: One hundred percent. Just leaving the land that you live on, and the people you buried in the dirt, just to walk away from the people that you love and the home that you built ... you have a certain toughness being from Louisiana. It wasn't a question of leaving. It's what we do in real life. These people would never leave that land.

So, it really does come down to, "We don't want your help. We can take care of ourselves."

Henry: Yes. Just like this last catastrophe we went through, we sat around waiting on our roofs, and no one came. We had to use our own survival techniques, because no one is coming to help us. There were days when no one was there. That's just the way we are.

What's been your personal experience of the reception of the film?

Henry: We knew we made a good movie, but sitting in there, with me never having acted before, I was worried as to how people would accept the film. I was sitting at Sundance, watching it for the first time, and I'm nervous because I don't know what kind of reaction we are going to get because it's a different kind of film. "Are we going to get booed?" But when the film was over, 1,500 people stood up, applauded and yelled. It felt so good. It felt so good that they all enjoyed the movie, it was amazing. And everywhere we go, even with Cannes, they told us the French audiences were much tougher, we went through the same thing: "We might get booed, etc." But we had a better response from the Cannes audience than the Sundance audience. It was a ten minute standing ovation. I almost lost it. I had to compose myself with all the joy that I was feeling inside. It was wonderful.