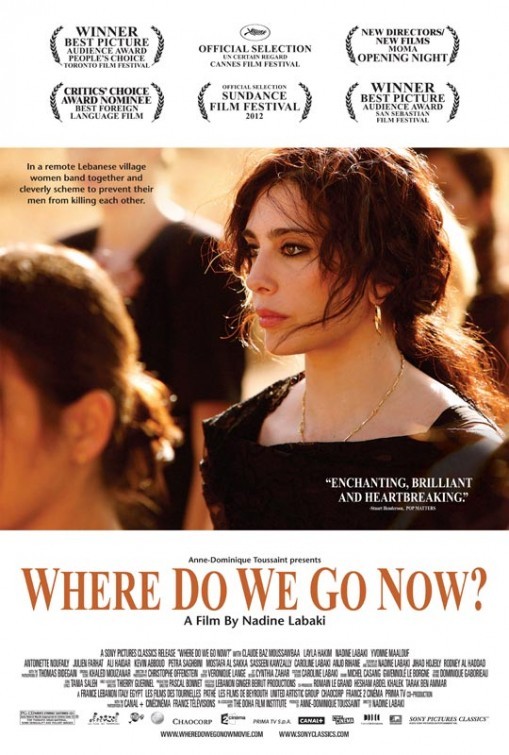

In the film Where Do We Go Now? writer/director/actress Nadine Labaki plays Amale, a shop owner in a small Lebanese village that has random surges of violent religious tension. In hopes of saving the Muslim and Christian men from ultimately destroying each other, Amale spearheads a wild plan to distract and disarm the men with the help of other wives and mothers in the village. The film is Labaki's second, (having previously done the acclaimed Caramel), and also marks another movie in which she chooses to act and direct alongside non-professional actors.

I sat down with Labaki to discuss her film, why she chooses to work with non-professional actors, and the impact that television had on her life when she was hiding from the war outside.

In the film Where Do We Go Now? writer/director/actress Nadine Labaki plays Amale, a shop owner in a small Lebanese village that has random surges of violent religious tension. In hopes of saving the Muslim and Christian men from ultimately destroying each other, Amale spearheads a wild plan to distract and disarm the men with the help of other wives and mothers in the village. The film is Labaki's second, (having previously done the acclaimed Caramel), and also marks another movie in which she chooses to act and direct alongside non-professional actors.

I sat down with Labaki to discuss her film, why she chooses to work with non-professional actors, and the impact that television had on her life when she was hiding from the war outside.

Where Do We Go Now? opens at Chicago's Music Box theater on May 18.

How long have you been doing promotion for this film?

A year almost. It first premiered at Cannes, and ever since then I've been traveling with the film. Usually it's like that - you travel for a year after making the film and then you stop to relax.

There's a lot in this movie about people experiencing television for the first time. What were the first films you saw when you were gaining an appreciation of movies?

Because of the war, we spent a lot of time at home. Boredom became a very big part of my life. To break that boredom I started to develop a relationship with the TV. Whatever was on TV completely fascinated me. Because of the war we didn't have power, but when it did come, it was like an escape from the reality of my boredom. I also lived right next to a video rental store, where I spent a lot of time renting films and watching them over and over. I decided one day I was going to make a film.

Any specific titles you remember really liking?

Grease. The fact that it was colorful, [and it had] interesting people. It used to make me dream.

Did you ever get around to watching the sequel to Grease?

Yes, of course. But I didn't like it as much as the original. I can recite both of them by heart [laughs].

Do you especially enjoy musicals?

I love musicals, because I am fascinated with dance. I take dance courses, and am fascinated with how much the body can express. It can go beyond language and culture. I wanted to experiment on that with my film.

How did you work with these non-professional actors?

The non-professionals did not have the experience of an actor; they don't take [the craft] very seriously. I'm at a stage in my life where I need to believe in what I am doing. I don't really like the word "acting" a lot. I'm looking for that moment of truth. I ask people to be exactly who they are. Most of the time, I don't give them anything to memorize. Sometime, they discover the scene as you throw them into the situation, and I just want to see their reaction to what is happening.

Was there any stiffness working with non-professional actors? How did you loosen them up in the camera?

I see them a lot before we shoot. We become friends, and I start understanding what makes them react in a certain way, and what triggers certain emotions. When we get to the shoot, they are very relaxed - they don't feel like this is some serious thing. Also, the fact that I am acting with them also makes it easier. They believe I am one of them. I am able to direct the scene from within. It's like a conductor - you are there with them. There's no distance. It becomes very organic, and very instinctive. It's not easy because it's chaotic, and the crew has a hard time following. They don't know if I'm giving instructions or acting ... but I like this chaos.

Was it a problem that people weren't taking it seriously when talking about dramatic scenes?

It does become a problem because they're not very disciplined. They don't know how concentrated an actor is on set. It is hard because you feel the chaos, you feel that there is a hurricane around you, that it's not quiet. The fact is that I took a subject that each one of us knows very well, so when it got serious everyone could relate. One of the most difficult scenes to shoot was the scene with her mother and receiving the body of her son. Everyone was emotionally taken - everyone has lost somebody in the war.

How did you go about balancing the differing tones of the movie?

It was very instinctive. Comedy and humor is very important in this type of situation. You need to address people in a way that leaves a mark in their head. Sometimes the situation is so absurd you can't help but laugh about it. When you look at your flaws, it's a way to start the healing process. We also needed to make the reason as to why we make war completely ridiculous. Tragedy was also a serious part, because it's not a joke. It was very natural.

It has a "facts of life" aspect.

Absolutely.

What did your two co-writers contribute to this story? How does your process work?

We work together through the whole process. It's an adventure; it's not like work. We talk, we discuss stuff. It's very pleasant. We only work when we are together, and we work from home. It takes about eight or nine months of writing.

You have a strong interest in collaboration. Is that something you always hope to maintain?

Yes. I hope so. It's important for me. It can not be work for me, it has to be a human adventure. Otherwise, it is not interesting. I have to share a bond. And with doing a shoot, I have to see how people are. You feel like everybody is there for you. I can't work in conflict; it paralyzes me. That's why I am scared in maybe trying different kinds of filmmaking. It works for me, but that doesn't necessarily work with other people, and it may not be the right thing. The people who had structure working on my film were completely lost, and I didn't know if that was good or bad. But because there is no film industry in Lebanon, you don't grow up and work on other films and see how they work; here is not a path. You are creating your own path because this is what seems logical to you.

How did your work method in filmmaking affect the editing process of the film?

It's never the same shot twice, it's never the same sentence twice. Because I am looking for that unexpected moment of truth, I try to trick [the actors] into doing something unexpected. To do that, sometimes you need to shoot a lot. [Editing] was hard. It can go so many ways. And during the editing, I choose the best out of everything, and try to create a scene with what I have. The result is not always what was expected in the beginning; it's different, and sometimes even better. It's frustrating sometimes. You are not where you want to be, but sometimes it's for the better. I think editing is 50% of the work, and maybe more. I love editing.

What happens to the young man with the glasses who brings media to the town in the unwritten sequel?

I haven't thought of that. Maybe he is the one who brings TVs to everyone in the village.

Quick Questions

Favorite fruit? Kiwi maybe.

What did you have for breakfast this morning? Pancakes.

Last CD you downloaded? Tania Saleh. She's my friend, I downloaded her CD to my cell phone.

Age of first kiss? 18.