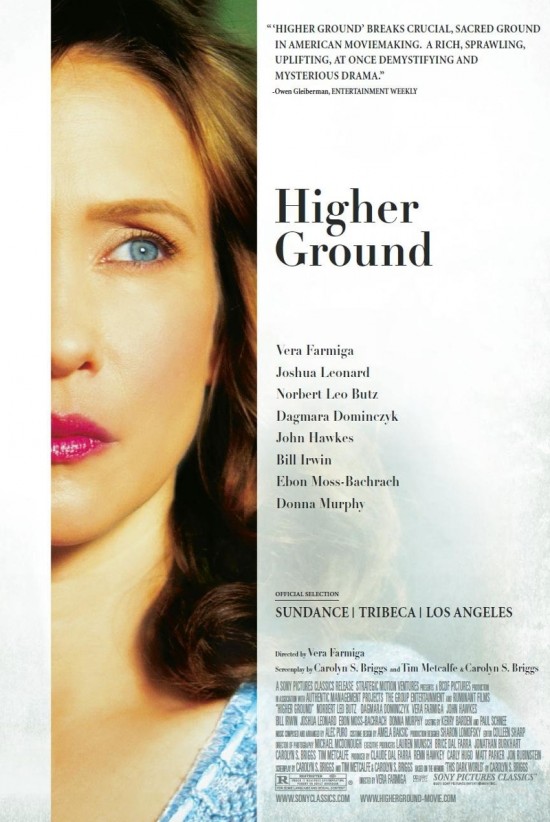

'Higher Ground' interview with actress/director Vera Farmiga

Oscar-nominated actress Vera Farmiga speaks in winding contemplative sentences, and sometimes even ends her thoughts with a bashful dismissal of her own thoughts. When discussing omnipotent subjects like spirituality, she seems to answer to her questions with more questions. Fitting it should be that Farmiga’s debut as a director, Higher Ground, should offer never-ending questions, with answers that we may never know. Starring in the film, she explores the life of a born-again Christian who sometimes falters in her spiritual strength. And like my conversation with her, Farmiga is about exploring the many curious factors of our entire existence.

Oscar-nominated actress Vera Farmiga speaks in winding contemplative sentences, and sometimes even ends her thoughts with a bashful dismissal of her own thoughts. When discussing omnipotent subjects like spirituality, she seems to answer to her questions with more questions. Fitting it should be that Farmiga’s debut as a director, Higher Ground, should offer never-ending questions, with answers that we may never know. Starring in the film, she explores the life of a born-again Christian who sometimes falters in her spiritual strength. And like my conversation with her, Farmiga is about exploring the many curious factors of our entire existence.

I sat down with Vera Farmiga in a roundtable interview to discuss the many concepts that fueled her desire to make her directorial debut, what it was like to shoot a film while being four months pregnant, and what her character Alex from Up in the Air might have been thinking during that movie’s heartbreaking moment.

Higher Ground opens in Chicago on September 2, 2011.

Why Higher Ground for your first directorial project?

I wanted to explore this character. This is the kind of character that actresses dream of. I wanted a meaty role. When you ski the bunny slope over thirty times you want some moguls. And this was a bumpy ride. And it had jumps and twists and turns. And I think it pumped some air in my spiritual life. The only way I could get it off its feet was to direct it. That’s the only way financing came … I can’t believe it’s coming out. It was a little experiment for me. I just gave myself a job. [Laughs] I picked a really big subject matter. [Pauses] G.O.D.

It’s as much about Hinduism and Buddhism and … we all have a different definition of it. I felt most familiar with this community, and felt I could represent it in a fair way. I wasn’t there to put my dukes and b*tch slap it. If I did, I’m sorry. But that’s not who I am. I think there’s so much wisdom to be received and perceived. All communities are flawed. All of them. Terribly flawed. Every single community we belong to. I wasn’t trying to make a film that had a belief about belief, not trying to determine whether God exists or does not exist, because I think … he does. We all have our own definitions, and experience as you will this film, but we’re all on that escalator to heaven. Whatever we think heaven is. Whether it’s a concrete place, or an idea. We’re all in that awkward climb.

This was the first time that you were involved with script supervising in a film, and you’ve said that you put your psyche into this story. What parts of you are in the story?

I think you’d have to dissect my brain. Look, I’m a mother, I’m a daughter, I’m a friend, I’m a parent, I’m a wife. Those are – yeah you can reduce this to a story about a woman and her relationship with God – but finding something within these relationships is something I struggle with. How do you persevere in these relationships? How do you retain your sense of self? Your identity? How do you continue to have passion within these relations? I related to [this movie] on many different levels. I’m kind of trying to determine what it means to be holy in my life.

Has there been an evolution as to how you see your spirituality since you were younger?

I remember going to confession. Ukrainian Catholicism, and not having any sins to confess. Completely making them up. And I didn’t even make up good ones. I told the priest once that I did my brother’s homework for him. I just couldn’t think of a better sin than that. This idea of what sin is, and what holiness is, is based on self-awareness. And self-perception. I know what my deficiencies are, I know what my strengths are. I know where I need more help. And that’s the spiritual journey. To know thyself.

Sort of like that monologue at the end of the film?

That monologue is a doozy. And that was the first scene out. And I had thought about every body’s characters in depth the night before, but not my own. I had a little freakout in my head, because there was very little time for pre-production. That was the threshold scene of the film, and that was first out. And I remember we did many different takes because there are so many different angles. Maybe because it was the beginning, we were getting so much coverage. Which is nice, because it’s good to have so many different perspectives of this monologue about truth and honesty, where she says “I don’t have all of the answers, but I’m loving the questions themselves.” I remember having to do it from cue cards at one point. I didn’t want to memorize that speech. It’s very much a scene about a woman finding her voice. She’s been so shut down by these relationships in her life, starting with her mother who diminishes her so she’s not musical. “You can’t preach,” etc. And finding the courage, or the voice, to state that. I made a point not memorize it, so I could figure out what the character’s struggles were. For me as an actress I was struggling. I have nightmares oftentimes about forgetting my lines. This was one of them. I didn’t memorize it … this scene is about having the courage to say it, and not submitting to everyone else’s ideas for you … I have no idea what I’m talking about.

You really see the stages of marriage in this film. The birthday party scene is a very powerful scene.

I chose actors who were extremely powerful. That speak volumes in silences. The one look between John Hawkes and Donna Murphy, those gazes of the “What If?”. This is a relationship that is quirky, and they have so much joy and so much love. Then they experience one of the hardest grievances that a couple can endure, which is a miscarriage. They don’t recover correctly from it. That’s the moment in which she’s sitting with her new husband, and there’s so much potential there. It’s like, “What if we chose to have faith in each other? What if we chose intimacy, passion?” Is love a decision? Do you chose to love someone? That’s what so agonizing about this scene.

I think it was written into the scene, and I was doing my own thing with Joshua Leonard. “You see black and white, and I see a whole lot of grey. We’re clashing right now. And you’re so dogmatic, and I’m not. You’re not stimulating me, and I’ve forgotten how to stimulate you.” Yet as a director, I’m sensing this very palpable thing happening. And he’s so brilliant, John Hawkes. When he just whispers something, which is kind of indistinguishable. But I’ve seen it in the editing room.

Do the children not see the subtext of this moment?

They do. They’re smarter than we give them credit for. Gabe, he’s such a sweetheart. Most of my children were non-actors. I prefer – it’s more like working with animals – you never know what’s coming your way. It takes a lot of footage to get those second-long reactions, and you get them from forty-minute takes. But you get jewels from them.

When you were directing yourself did you find that you were harder on yourself as an actor, and what is it to edit yourself? Is it easier or much harder?

I do what I do as an actress for myself. I directed other people, I didn’t really direct myself. I always direct myself. The relation that I was missing was someone watching my back saying, “You tried it that way, try something else.” And there are a couple of moments, I won’t tell you which ones they are, because people will be like “Ahh, she should have tried something different,” but there were other sources for me, members of the crew that become your confidant. Concerning what’s working or what’s not.

Did you have playback?

I didn’t utilize playback, because our camera was always on the move. Our playback was associated with A camera. But you know when you have it. You know when a crew is engaged. The camera operators, that’s who I go to first. Even in my acting work. I always look to them to see how engaged they are. Because they’re right there. They’ve got their eye on you. You can tell whether someone is invested or not. Directing myself, it was the editing that was the challenge. I had a great editor who would say, “You sucked there. But you looked pretty.”

This is a movie of ambitious tone. It doesn’t fit into a genre, and it’s about a character going through an interior struggle. Could you talk more about bringing to life the inner life of a character to screen?

It’s not like I had this tone meter which would start squawking … I think it’s a combination of Carolyn Briggs’ sensibility and mine, and the way we choose to look at things. Sarcasm is not indigenous to my personality, I’ve had to cultivate it. I think the fortes of my personality is the way I look at and experience this community. I tried to look at things in a positive way. “Here’s wisdom.” I don’t discard other people’s passions or investments, if I don’t understand it. I just try to understand it. So with tone, I think that if you tone to be respectful, not make mockery, and be in it, and not ride above it, and then you allow your own personality and your own sense of humor into it. … You lose your words, as a mind. I’m surprised I’m having a conversation with you guys. It’s tough.

The way she deals with so many things is to have fantasies in her head. But that’s the combination of Carolyn Briggs and myself. Things that titillate us. That put a smile on our face. And tone was there from the start, with Carolyn’s writing. I think Carolyn’s intention in journey was that this was a real life, it wasn’t a biopic, but we used it as a springboard. It’s her quirky search for holiness, and spirituality.

I don’t know though, I think some of the best films are spiritual. Down to the Bone was that for me, but just set in a different arena of long-suffering and persevering in addiction. And how to be the best mom that you can be. But with the shackles of addiction. It’s still a yearning for that best sense of self. The highest self that you can be. That yearning is holiness. This is just blatantly set in a spiritual community. I’m told there’s a lot of spiritual and religious based movies at the moment, but that’s what movies are.

When you were making this film you were five months pregnant.

Four months. I was five months by the time I started editing.

Did that at all have impact in an inspirational sense to the project? Did it make the work more difficult?

The pre-production was arduous because of morning, noon, and night sickness. But the filming of it, I tapped into some Mother Earth energy, and during my second trimester, and I can say that my daughter even at nine months gets it. She’s a powerful woman. I know I had her energy. There was something else. There was something that was fueling me. I’m biased, but I know she is pretty special. And I know that there are two hearts beating in you, containing another soul. But I know she is going to do amazing things in life. Just knowing her for nine months. I was operating with more moxie than I usually have. And I did complain, I hemmed and hawed. But I hate when I do that. Because it’s so rare to get a film financed, especially with everything stacked against this movie. It’s not easy to market, etc. I think there was a lot of strength to draw from. A lot of people who say that this was ballsy. It was pretty uterus-y.

But it’s not like you could cut back on the work, you had to condense shooting schedules, etc.

Yeah, I demanded 26 days. They wanted me to do 21 or 24 days. I said, “You gotta cut me a break. There a lot of hats on here.” And it was my first time. And I think I had a lot of slack on my leash because of that [Oscar] nomination. It does help. I had carte blanche, I could choose my cast, and not think of what would sell this film in Korea.

Did this project exist much before your nomination?

The script had been [brewing] three years before I came onto it, and three years before it got financing. Tim Metcalfe was gonna direct it. He’s the writer of six years worth of drafts. I collaborated with him for three years, he made connections with Carolyn Briggs, and then I pulled myself away ,and tried to wriggle myself away from it. “It’s not finding financing, its’ not finding its footing. I got to be more careful as to where I put my foot down, with my two kids now.” When I tried to wriggle away from it, it grasped me tighter. Then Tim suggested that I direct, and financing came within a month.

When was that?

[Laughs] Right around the Oscar. That was the time to take advantage. And I knew I was down for the count, because I was knocked up. So I needed to focus on something where I could take matters into my own hands.

I always think of you when I think about Up in the Air or Orphan. You project some level of strength or intelligence in any scene.

[Laughs] I don’t think of it that way. The only way I can think of a scene is, “How am I going to draw the best performance out of my scene partner, and the idea of, ‘Please do that for me too!’” The only thing I can focus on is playing some truth of the moment. Sometimes it’s not obvious.

I think I heard that you said you need to find in a character something that you recognize or you want to defend.

Or sometimes I don’t understand.

How could you go to the wedding with the family in Up in the Air? What do you think about that?

I know first hand what that’s like. I’ve experienced it. It’s awfully painful. I think many of us have. I think it’s kind of easy to put ourselves in that position. Again, it’s how do you stay stimulated? How do you stay true? How do you unconditionally love someone, and not lose your sense of self? It’s a very painful position to be in. The audience is privy to only one perspective of it. Alex, I’m sure she went home and probably weeps and screams and I think that there’s a whole dimension that’s not in the film. We only see her having fun. And that’s why the shock comes in. And it’s a real smack in the face. And in an unapologetic way. That’s why it’s so hardcore. “Don’t come here. This is my life.”

Did you ever think about playing that scene in a different way?

I gave Jason [Reitman] a couple of different attempts in the car, when she’s calling him. I gave him a quiver. Several times. And he said, “No, no, no, don’t apologize.” And so that was his direction. I really said, “Let me try several different attempts at conveying this information.” And those didn’t work. … Women love that moment. They’re not saying, “Yay! Look how low she is!” But I think they identify with this sort of – well, first of all, anyone who is unapologetically themselves, is a bit reckless. I look at it as a two-edged sword. But I’d love to see a film about Alex, and what happens when she goes home. There’s a whole mystery to the character, that we can only intuit or perceive based on our experience or family lives. Who’s to say that our husband doesn’t make her do it? There are so many possibilities. Or what if that’s their deal? You never know. You give them the benefit of the doubt. Aren’t we a quirky lot?