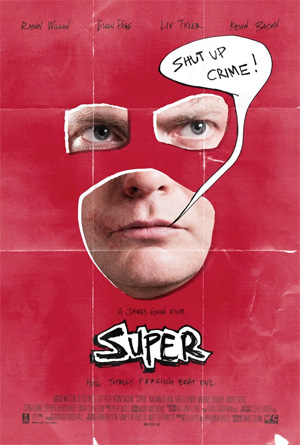

Super is, as James Gunn tells me, "about a guy who is on some sort of spiritual quest, and he just happens to wear a superhero costume during it." The film features Rainn Wilson and Ellen Page in their craziest roles so far, and parades a rate of violence more similar to The Toxic Avenger than Kick-Ass into the new subgenre of superhero movies that explain what it really means to be a caped crusader. However, at the end of this extensive interview, Gunn tells me, "only I know what this movie is." I sat down with Gunn, writer/director of the IFC Midnight film Super, in a roundtable interview in Austin, Texas during this year's South by Southwest Film Festival. With the interview taking place the day after its SXSW premiere, topics included Rainn Wilson wanting to avoid "Dwight-isms," how this movie came before Kick-Ass, the possibilities of James Gunn writing a Dawn of the Dead sequel, and more.

Super opens in Chicago on April 8th at the Music Box Theater.

There’s a lot of entries into that self-reflective comic book movie scene, with films like Kick-Ass or Special. Were you aware of that, or wary of that?

I was aware of it, because I wrote my script in 2002, before all of those things. The first thing I heard about was Special, because Special was written after that, and my movie was out there, and we actually had funding from a different company at the time. I heard of Kick-Ass from Mark Millar, who is an online friend of mine, we’ve been e-mail buddies for a long time. He said, “What are you doing?” I said, “I’m getting this movie called Super made,” and this was back in 2004. He said, “What is it?” And I told him, and he said, “Oh f**k, I’m writing a comic book that’s kind of like that.” I was definitely wary of it. And then Kick-Ass was made into a movie, and I didn’t know if we would be irrelevant. The stories are so different. Our story is about a guy who is on some sort of spiritual quest, and he just happens to wear a superhero costume during it. Really, the story could be told without the superhero costume, which is like gravy. And frankly, it probably helps the movie get more attention than it would otherwise. But it really is about the guy, not the costume.

Where did your concept for Super come from? Are you a comic book fan?

I’m a huge comic book fan. I’ve read comic books ever since I was a kid, and I still read them. I read almost every comic book that comes out. I love comic books. I’m enamored of superheroes, I’m interested in how that plays with our own lives. Super is a lot about pop culture, and we view whether its superhero or celebrity, or whatever we see as a part of that pop culture world, it’s something beyond us. This is about a guy who tries to enter that other world that is so impossible, and does so with some degree of success.

You said that you wrote the script in 2002 – why did it take so long to get the script into production?

Number one - in 2004 I had Chuck Rogan producing the script who did the Dark Knight movies, and my Scooby-Doo movies, and it was a little esoteric. He wanted me to cut back on the violence a lot. The biggest thing was, there was a company that was financing it. There was a list of people that could play the role that [the company] would OK. There were a lot of actors that wanted to play the role, but the only person I could see playing the role at the time was John C. Reilly. He wasn’t considered a big enough star at the time to get the movie made. So, I couldn’t agree on an actor. We were still gonna make the movie basically, but we hadn’t gotten to the point where we could cast the right actor. I needed someone that could do the comedy, could do the drama, and was big enough that he was physically threatening but also goofy enough so that he could be picked on by his fellow short-order cook at the diner. It was hard to find somebody like that. At that point, I wrote the movie Slither, which I was going to sell and just make a few bucks, so that I could off and make this movie for no money. When I went out with Slither on a Thursday night, and Friday morning Paul Brooks, who ended up producing the film, said, “I want to greenlight the movie, and I want you to direct it.” So that’s what I did. That put a hold on things for a while. And after Slither, I wasn’t even sure if I was ever going to direct another movie again, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to, I wasn’t’ sure if it was worth it to me, and I started doing web stuff which was a lot more simple. It’s hard making a movie. You lose your life. I like being alive. I like having friends. And I like going out, and I like watching other people’s movies, and all these things that I can’t do for a year while I make a movie. And then it comes out, and it’s like, “So what?” I don’t care, I don’t get any joy out of you liking my movie – that’s not true – I like when people like my movie, but as a kid growing up, it’s like, “I really want to make everybody love me, and have people like my movie, and go to film festivals, and be interviewed by a bunch of people at a table.” None of it gives me joy, not in real life. I like making the movies, sometimes, but it’s also hellish to make a movie.

So I’m a very confused individual. It wasn’t until my ex-wife Jenna Fischer called me up one day, we’re still very good friends, and said, “What are you doing with Super? Why aren’t you making that movie? I love that script, it’s my favorite script that you’ve written. I want you to make that movie.” And I said, “I don’t know. It’s a little esoteric, it’s weird, my manager doesn’t want me to make it, I’m not sure,” and she said, “Have you ever thought of Rainn [Wilson]?” I had known Rainn for five years, we had always gotten along well, we had a sort of camaraderie, and it was like, “Wow. That works.” From that moment forward, I just sort of felt called to make the movie. I had my heart in it. It made all the difference from all the things I’ve done in the past, because I feel really good about the movie. I would love for other people to love it. If they don’t, that’s okay too. It’s a great experience. Having those other actors put themselves into the movie so completely for literally no money, I mean, Liv Tyler got paid $7,000 to do this movie. For them to do all of that for me and for this project is a really great experience. That, and also people like Steve Gainer, the cinematographer. We had a real connection on the set, and he knew exactly what I wanted. Or Tyler Bates, who did the score. It was a really good experience.

So he calls himself the Crimson Bolt, and walks around with a pipe wrench. I was curious what inspired you to include those elements.

I don’t know where the Crimson Bolt came from. I think it was just a first name. I remember, in my first draft, he went through different names. Somehow he arrived at the Crimson Bolt. One reason that’s helpful is because I did make another superhero movie called The Specials, and it’s very hard to find superhero names that aren’t already claimed. And the pipe wrench is something that I wouldn’t want to be hit with.

The thing that strikes me most about Super is that it’s really dark and messed up, but it’s also a very optimistic film. It feels like it does believe in the possibility of changing the world.

I think that one of the things that drives me in telling stories is finding the beautiful within this big massive ugly. So much of people, especially living in Hollywood, is really ugly stuff. I guess I am an optimist in a pessimist brain. I believe in people, I believe in the innate goodness in most people in this world. And yet I’m a damaged soul like a lot of people, and I have things that I struggle with. I can’t be told that life is beautiful through a normal positive thinking book, or a Hallmark movie. That language doesn’t work for me, the language for me is the language of f**ked up cinema and comic books, and things like that. To find the beauty I really need to go through a darker channel.

I think you see that too because Frank doesn't really get the happy ending. Through somebody else, he achieves some happiness.

To me, he does have a happy ending, but it’s not happy as how we think of it. We think of happy as acquisition, you get the girl, you make the million dollars. But at the end, he only had two moments in life that he thought made life worth living. At the end, you see that he likes driving the toll booth. It is a happyending. He sees the magic in every moment. Yes, he’s a lonely guy, and his only friend is a rabbit. But he can find happy moments.

TSR: There’s a lot of frank violence. [During a pivotal, brutal death in the third act] do you want your audience laugh?

Were you that guy laughing? Here’s the thing about Super. That’s the fun of the movie. An easy moment to explain is when he’s saying his prayer. That’s always a weird audience, and it’s maybe my favorite scene in the movie. All the stuff when he’s talking about his hair etc. is so, so, so sad. And so funny at the same time. And so some people are laughing, and other people are getting mad at those who are laughing. That’s exactly like what that scene is intended to be. It’s meant to all those things mixed up together. That’s up to you. You’re weird. I’ve screened this movie many times, and I’ve had people chuckle at that, but I’ve never heard anyone laugh hysterically except for you! I had 2,000 people here, 2,000 people in Toronto, 2,000 people in Italy, 2,000 people in Spain, and so far we’ve had about 10,000 have seen the movie, and one person laughs hysterically, and that’s you.

TSR: Were you laughing when Frank kills a character the corner of a fireplace? Is that funny? It hurts!

[Laughing] I think he goes a little far. There’s something humorous that he keeps smashing the skull when the guy is obviously dead. I guess there’s a funny element to it. But it’s also really sad. That character is the one element of those thugs that actually has a little bit humanity. We see moments in which he feels bad about Liv Tyler being dragged into the other room. He’s an evil guy, but he’s not [the others]. That moment in which you’re watching the Crimson Bolt and you’re like, “… I guess that alright.” That’s more my reaction to it. What’s the other thing you laughed at? I don’t laugh at that [other particular scene]. There is an element of humor in the fact that it’s not what people expect.

One of the difficulties in getting this made was people telling you to tone back the violence, or make it less strange. Is there anything you had to scale back on? Or did you go all out?

All out. I stupidly tricked the producers by saying, “Look. People are going to like this movie because it’s extreme, or they’re not going to like it. So if we start pulling back on things that are extreme, that means we would be pulling back on the things that some people are going to like, and make it a nothing movie.” So I tricked them, and got to do what I wanted, basically. But honestly, I had this cast behind me, who was all signed on because of the script, who were doing it because of me. We were all doing this movie for nothing, the reason we were doing it is because we wanted to make the movie the way we wanted to make it. And so a couple of million dollars, with that amount of talent attached, is a rare thing.

Frank’s hallucinations are really cool, stylistically. I was wondering what inspired them.

God touched my brain one time. You think I’m kidding, but I’m not.

And the tentacles too?

No, no the tentacles, but the bigger guy came and touched my brain. That part is real. I think I really liked the mix of the spiritual and the visceral. In the script it even says “Cronenberg-ian.” I really like that mix. It’s something I’m interested in. There’s a book called the “The Varieties of Religious Experience,” written by William Jameson in 1904. It’s about people who have religious experiences, and a lot of these religious leaders have spiritual awakenings. Is it something from an actual problem in your brain? Whatever it is, I have it, because I’ve been having visions since I was a kid. I think that’s a big part of what the movie is about.

So what’s next?

I have this movie called Movie 43 that we’re finishing up. It’s a comedy by the Farrelly Brothers, and features different comedy directors working with different actors. Everybody from Hugh Grant to Kate Winslet. I have Elizabeth Banks and Josh Duhamel in my segment, and it’s a lot of fun. It’s really extreme, like this, but it’s full out comedy. But it has a lot of heart to it. I have that, and I just finished a script.

Is there any potential of another Dawn of the Dead?

No, not really. Years ago, Zack [Snyder] and I sat down and talked about doing Dawn of the Dead 2. We actually had soft of a plot for it, but I don’t think it’s … it’s something we could do if we wanted, but I’m not feeling the zombies right now. There are so many of them. It would have to be something very different. There are zombie tales to be told, but I don’t think if I ever did a zombie movie, it would be Dawn of the Dead 2.

There are some really fresh zombie projects out there.

I read the script for Pride and Prejudice vs. Zombies, and that could be alright. I like The Walking Dead a lot.

I think you did a great job with inverting of what you would expect from Ellen Page and Rainn Wilson. Was that difficult to do, or was that one of the reasons you wanted to cast them?

It wasn’t the reason I wanted to cast them. It was something I was wary of from the beginning. Rainn said to me at the very beginning, “Listen, if I do something that is a Dwight-ism, just pull me aside, and tell me that I’m doing something Dwight-ish.” There were two times during making the movie when I told him he was doing something Dwight-ish. He had been playing that character for a long time, and I think the main thing for Rainn was to have that sense of vulnerability there. Dwight has a sense of vulnerability as an idiot, but he’s not a vulnerable guy. Frank is very vulnerable. To really bring out that vulnerability was really important for him. For Ellen, what really attracted her to the script was she said to me, “For years, I’ve been asked to play these characters who are wise beyond their years. These snarky teenage girls who say these things that are one-up of the adults around her.” This character is the exact opposite. She’s a 22-year-old with the maturity of an 11-year-old. She’s completely wrong in every way, and says whatever is on her brain. That is what brought Ellen to the character as well – the energy that was crazy madness that she is usually more lowkey. I was aware of who they are, and I think as actors I think it’s important for them to create other archetypal characters who are not the ones who they are associated with.

TSR: Another great performance comes from Nathan Fillion. How easy was it to get him on board with Super?

Nathan’s my good buddy; we hang out a lot.

TSR: Did he high-five you when he read the script?

Nathan would just do whatever I would ask. I thought he would be perfect [for the film]. When I first wrote the script, I thought it would be good for Bruce Campbell.

TSR: He’d have to do the Superman swoop though, not Nathan’s long hair.

The long hair was Nathan’s idea. He came in, and we fit him for the costume. That costume cost more than the other costumes because it’s actually kind of a real costume, with the fake muscles. And Nathan said, “I think it would be great if I had some long Jesus hair.” Nathan’s funny, I love working with him. And I love working with these people who are my friends It’s hard making a movie but to have people like Nathan or Michael Rooker, it’s really nice. I write Nathan these roles, and whether it is Slither or PG Porn or this, he always brings something beyond what I expect from the role. He always goes beyond the call of duty. One of the greatest film actors around. It was great to work with him.

This movie is a mix between IFC and Troma.

That’s how I think of the film. It’s an arthouse head on a Grindhouse body.

There are moments of total deadpan-ness, and then there are Troma moments. Were you nervous about bringing those elements together or were they always in the script?

They were always in the script. I didn’t rehearse the movie at all. We didn’t’ have the budget for that. That was always apart of it, to be able to mix real people in situations with exploitation elements. But I wanted to keep things real and grounded. But with Troma movies, and Lloyd [Kauffman] will admit this, the acting is pretty atrocious. Tromeo and Juliet, I tried to write for bad actors, so the bad acting would be a part of what we enjoyed in the movie.

I like Tromeo and Juliet.

Some people are good. Basically, any actor over thirty in that movie sucked. That’s not true. But, it’s something you have to deal with from the beginning. In Super I didn’t want to deal with bad actors.

Can you elaborate on how grueling the shoot was?

We shot for twenty-four days. Most movies you shoot between twelve and twenty camera set-ups a day. We were shooting between forty-five and fifty camera set-ups every single day. That means fourteen minutes between every camera set-up. We hardly had to wait on camera. We waited on props more than camera. We had to create what we called on a set a “culture of speed.” Which means we needed to have the speed work for us as opposed to against us. We wanted that sense of urgency to be something that fed the film as opposed to detracted for it. I had a very explicit, specific shot list for the movie, all of which was in the film. I only lost one shot throughout the whole shooting, which bums me out to this day.

What was that shot?

When Rainn is getting beaten up the thugs outside Jock’s car, there’s supposed to be a shot from the back of a van where we pull away from it really quickly, and go into the next shot. I couldn’t get the van shot. Small thing to the world, big things to me. But basically, we got everything we needed, but it was through careful choreography between me and Steve Gainer and our AD, Sherry.

Did your Troma experience help you with this?

There’s no doubt. Troma taught me everything about that. One side of my brain have my director’s side of my brain, the other is the producer’s side of the brain. The producer side doesn’t fight the director’s side, it helps. Because if I was just doing things as a director, I would lose shots. I’d be so focused on getting one scene the way I want it to be, that I’d take too long in the day and lose shots. Through the experience of making movies for a number of years, I had to learn how long it takes me to do something, so that I can take less time on things that are less important, and take more time on the things that are more important. And give the actors time to breathe at times. Those guys would give a great performance, I needed Rainn to give a good performance for [the prayer scene]. I needed the right amount of time to get all of the shots I needed at the end of the movie, with all of the gunfire, there’s a lot more shots than compared to the rest of the movie, and I had to be able to give appropriate amount of time. If I just rely on an AD or a line producer to schedule that amount of time, it’s going to go all wrong. It really has to be me who does that, because only I know what the movie is.