Fresh off his "Best Director" and "Best Picture" Oscars from 2008's Slumdog Millionaire, Danny Boyle returns to the silver screen with an arguably smaller story, but one with equal spirit. Adapting the courageous tale of hiker Aron Ralston, Boyle has crafted a unique film that doesn't go without his classic touch, however unlike his previous movies it may seem. Guided by the mind of Boyle, 127 Hours becomes much bigger than the survival story of a man with his hand trapped underneath a boulder.

Fresh off his "Best Director" and "Best Picture" Oscars from 2008's Slumdog Millionaire, Danny Boyle returns to the silver screen with an arguably smaller story, but one with equal spirit. Adapting the courageous tale of hiker Aron Ralston, Boyle has crafted a unique film that doesn't go without his classic touch, however unlike his previous movies it may seem. Guided by the mind of Boyle, 127 Hours becomes much bigger than the survival story of a man with his hand trapped underneath a boulder.

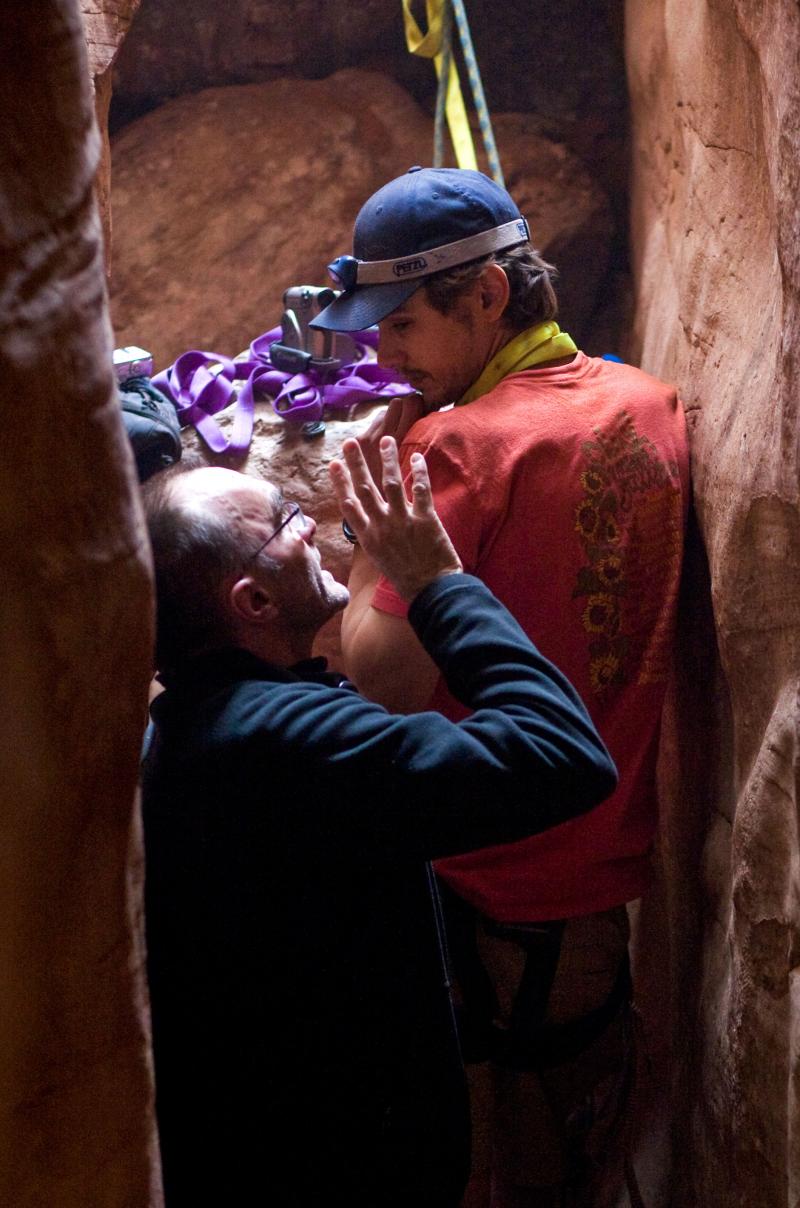

I was able to briefly get into Boyle's brain during a roundtable interview at Chicago's Elysian Hotel. My second interview with the now Oscar-winner, he maintained the same "nice fellow at a pub" amicability I felt the first time we discussed his work (and I also thanked him for Sunshine). This round, Boyle revealed that the most of the thought about a film occurs after it's been made, and especially for press events like this. We also discussed other topics including controlling the mood of the story, the importance of sound design, whether he would direct that third 28 Days Later sequel, and more.

127 Hours opens in Chicago on Friday, November 12th.

[Doing these interviews] is your favorite part about making movies, right?

I actually quite enjoy it. It’s funny. When you’re making a film, you don’t really think about them in an eloquent way. You have to develop that in promoting them. You suddenly discover things that are a bit unformed, you have to kind of form and present. The better you can do it, the better it will help because it makes a better article or whatever it’s being used for. But it’s kind of interesting, as well. You have to find it interesting. Otherwise, you look like an ass. People come a long way to talk to you for ten minutes, and you just look like you’re bored out of your mind.

With a film like 127 Hours, it would be so easily to go the depressing route. You make it so full of life and joyous, which you do with a lot of your movies. Was there any point where you were torn between which route to take?

I don’t think anyone would go and watch it [if it were depressing]. To be honest, I wouldn’t go and watch it. I’m not a shiny happy person. I’m optimistic about life. I believe in that force that is there. I don’t believe it’s individually based, so much as collectively based. I wanted the film not to be about Aron Ralson, the individual superhero. To be honest a bit, the myth about him, and much of those guys – in fact, when you really look at their stories, they are really about the communality of people. In fact, when I looked at his story really closely, you can see what happens. When he walks through the canyon as an extreme individual, completely self-sufficient, doesn’t need anybody and does everything solo, and even when he’s tempted by girls to the party, he just runs off. He’s the complete individualist. And what happens if he gets stopped by the things that he worships, and imagines that he’s one with nature. It just stops him. It forces him to look at another part of himself. He can’t move that boulder. And he has to ask, “Why can’t I move that boulder?” It’s because he has to look in himself. He has been not cruel, but he’s been careless with people’s affections. He’s 27 and guys are like that. When he really looks at himself, this image pops out, and it’s a child. And he knows – this is in the book – he absolutely knows its not religious fantasy. It’s not Jesus. It’s his child. The last thing he’s thinking about is that he doesn’t want a kid. He doesn’t want a stable relationship or anything. But it means he has a part to play. That part to play is not to be a superhero, but what we all play in the end. You live a bit, and then you pass it onto someone else, and then you die. And that’s it, basically.

On the bookends of the film ...

That’s why the film begins and ends with people. Even in the loneliest place. And the most important line in the film, [there’s this] incredible superhero who sees these rather dogs in the distance and screams “ I need help,” and he does and we all do. It’s what I wanted to make the film about.

You’ve expressed specific interest in survival in extreme environments. I was wondering where does this interest come from and how does it relate with your relationship to the outdoors?

I have no relationship with the outdoors.

No hiking or anything?

We shot for a week in Long John Canyon where he got trapped. It’s sort of inaccessible, and you have to camp there. It takes so long to get there, so we camped there for six nights and six days. I realized when I was lying there in the middle of the night that it was so quiet, and really scary. There are no sirens, people shotungi in the street. I thought, “It’s been thirty-three years since I went camping. And I would be very happy if it were thirty-three more.” I love cities. I love Chicago. I love this job. I was [just] in Boston, amazing city. I don’t want to go to the wilderness. I’m quite happy living in cities, in these mindfuck places we’ve created for ourselves. And they say movies are escapism, you’d think we’d all go watch films about the wilderness. No one watches films about the wilderness. If this had been about the wilderness, nobody would go and watch it. We live in these cities, we go to multiplexes in these cities, and watch films about all these cities.

What about The Descent?

It’s an urban film, really. It’s a community of people under siege. It could be happening in an abandoned tower block. What they mean by wilderness film is that you’re communicative with nature. And we’re not interested. All cities are growing – well, a few places not so much. People don’t want to live in the countryside, they want to live in the city. That’s what we are as people. That’s what we do. I find that life spirit expressed in extreme odd stories, where you are against the odds. And I find what we were saying about “Why do it joyously?” that life-affirming spirit I find in those stories. I’d much prefer if they were set in cities, but they can’t all be, so I have to go camping.

What did you do when you were out there?

I did rappelling. It was terrifying. You’re on a cliff, and it’s like one hundred feet down. You’re holding onto this rope. You have to lean back into this harness. Your instinct is not to lean back. Once you do that, it’s okay. It’s a cool feeling.

In this movie I noticed your sound design is very loud, very distinct. When you read a script and write a script, where does the sound design fall in, and how much room do you give that sound designer?

When we started out making the first film, we had a million pounds to make that film. One of the things we did, we talked and said at that time, “Why is it that British films are so disappointing?” It’s because you go to cinemas and watch American movies, and then you’d watch a British movie. One of the extraordinary things about the American mainstream films is the amount of money they put into sound. They know, as I know now, that 70% of the experience in this so-called visual medium is sound. If it’s out of sync, you’ve lost three minutes. Then they walk out. So we ear-marked money, and even though we were running out of it, and we had to sell off bits of the set to get film stock to tell the story, we had money for sound which we didn’t touch. It delivered the film. We’ve all carried that idea ever since, and it’s easier now beause you get more money. We have a guy in London who does it, called Glenn Fremantle. When we did Slumdog, we got a lot of nominations. And the only person that didn’t win was Glenn.

Who won sound design that year?

It was Batman. We did one sound, the mixing thing, but there are two categories, and he’s in the other category. He is extraordinary. [Sound] is about creating a landscape and intelligently and organically to the film. And then we try to use the music, and I love pop music, and pop culture. I find it really valuable. It’s sneered after by people. When you hear a new pop song, it gives you a feeling that high art can’t give you. You feel alive again. The first time you hear a song by Lady Gaga, you think, “Who the hell is she?” Or that Janelle girl. It makes you feel alive.

That’s what your scores try to do, bring people out of your seats?

Yes. It’s like that.

I’ve read that you have seen Ralston’s personal footage from the actual events. How did it inform how you wanted to tell the story, and did you try to repeat the same shots?

The video messages are all the same, we use the same camera. A lot of the messages are verbatim what he said. It’s quite clumsily expressed sometimes, but that’s what we are in real life. You’d never write it like that, but we kept it like that. The messages themselves were weird because he was very reluctant to show them, he has only shown them to people he was very, very close to. Because of that I was expecting them to be abject, or pitiful. Crying. In fact, he tries to make himself look dignified as he’s dying. But with James [Franco also], you can see this is a guy who is looking straight at you, and thinks he is dying, and thinks he will be dead. And there doesn’t appear to be any avenue out. It’s weird, that level of control. Trying to stay dignified. He did admit that he had gone over some messages that weren’t so controlled, and replaced them with self-controlled ones. He was very conscious of not wanting to, particularly his mother I think, he didn’t want his mother to see him in a terrible state. He leaves these messages every twenty-four hours, and the tape doesn’t even jump, it just flicks to twenty-four hours later. You can see he’s decayed. The twenty-four hours after he has run out of water. He just shrinks. It’s not like carbohydrate weight loss, it’s different. It’s like whoa. The only way we could do that is through CG, which I didn’t want to use. You can’t get actors to – you can get actors to starve themselves like Christian Bale did The Machinist - but water you can’t do it. The medics tell you that if you don’t have water for a day you can die any moment. It’s not like food which you can live sixty days without it. One day your organs are going to collapse. And once you get past the twenty-four hour period without water, the brain starts to get loopy, you start having hallucinations. The brain starts to get loopy.

And what about the rumors that you’ll direct a sequel to 28 Days Later?

Certainly, everyone is going, “Oh, you are doing it!” There is an idea. I’d really love to direct it.